Iwona Dakiniewicz,

[with assistance from William F. Hoffman]

The specifics on Polish cemeteries cannot be summarized in a few sentences. It is a subject like a river, as long as the history of Poland. I have confined myself to the information that is most essential, most necessary for genealogists to know.

Anonymous graves are scattered all over the landscapes of Polish cemeteries. Polish cemeteries are like a kind of museum; they reveal the history of the region and of the whole people. Polish was a nation of many ethnic groups and faiths. All the different religious and cultural communities were concentrated in churches. As a rule a cemetery belonged to each church. Necropolises of various faiths in a single gmina were not rare, however. Most often these were Roman Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish cemeteries. In the south and east Greek Catholic, Orthodox, and, less often, Muslim cemeteries are to be found.

Tombstone Stefcika Kamieńskiego and Maniusi Lipowskiej. Jan Woydyga, 1890, Stare Powązki

http://www.cmentarium.sowa.website.pl/Cmentarze/Anioly05c.html

History has treated all the cemeteries cruelly; the destructive force of time and numerous wars have left their mark. Of some there is not even a trace left; others can be found only with the help of a local guide. That guide might be a sołtys [a local administrative official], a priest, a local chronicler, or a historian. It is a good idea to take along a scraper, pruning shears, or other gardening tools. Lost graves are overgrown with weeds or moss, and may be overturned or broken or buried by layers of sod and roots. Old, forgotten cemeteries may be located in forests, on hills, in meadows, or, less often, among town buildings.

World War II and the decade after it was a time of the greatest destruction and devastation of cemeteries. During the war, Catholic and Jewish cemeteries suffered the most. The postwar period was devastating for Protestant cemeteries. That was a form of retaliation for Poles after five years of German occupation.

Cemeteries of other faiths, in turn, were affected by the political and ideological systems of the times (for instance, Akcja Wisla [Operation Vistula] in 1947). The Socialist government gave permission, to some extent, for plundering what was left behind by „those who were evicted.” In practice this took various forms: materials for construction from dismantled churches and cemeteries were exploited by local informers, for instance, as a way to get rich quick, or by parish groups for modernizing villages (bridge or road construction), or by common criminals for illegal trade.

By far the most cemeteries are Roman Catholic. Beginning in the 10th century, they were located on church grounds near the sanctuary, the parish’s central point. Beginning in the 14th century, cemeteries were established outside the limits of specific localities for those who professed other faiths.

Close proximity of cemeteries to dwellings, however, had an unfavorable effect on the soil and on the water inhabitants drew from their wells. As early as the late 18th century, sanitary regulations began placing more and more restrictions on burials in churches and their vicinity (places were reserved only for clergymen). Along with a growing population, cemeteries began to be crowded. These were the main reasons for establishing cemeteries on the outskirts of communities.

There are also „occasional” cemeteries: graves of fallen soldiers, war heroes, those who died in exile, as well as so- called plague cemeteries (for the victims of epidemics). They are witneses to one-time events, facts from the history of a given region.

The spatial structure of cemeteries usually follows some sort of appropriate plan, most often with pathways in the form of a cross, and at the crossing point there is a chapel or an actual cross. But there are other arrangements: for instance, paths radiating outward. Several times I have seen a curious arrangement of the graves: all of them faced toward the church.

Large cemeteries were situated on hills. The significance of this was both sanitary (protecting the waters deep underground) and symbolic (nearer to heaven).

As a rule there is no chronological order; graves are mixed as a result of destroying old graves and acquiring new plots. Sometimes there are sections for children’s graves and modern graves.

It’s not rare for old, forgotten monuments to stand on the fringes of cemeteries. Lone, nameless crosses are a common sight in Polish cemeteries. Sometimes these graves and monuments are cared for by municipal services, Catholic unions or societies of historians.

As they lived, so they were buried. The manner of memorializing the dead depended on several factors: local culture and customs, the predominant fashion at the time, relative wealth, and available resources.

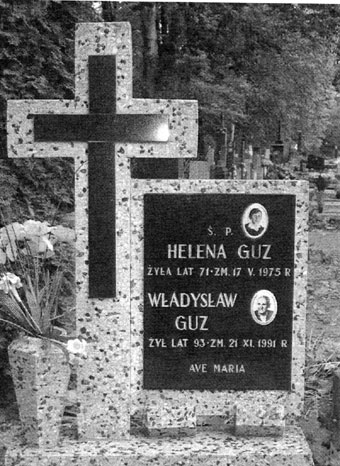

The inscriptions were mainly utiliatari- an in nature. The inscriptions can generally be divided into three groups: informational, emotional, and poetic (these are encountered less often).

There are two kinds of informational inscriptions: complete and abbreviated. A complete inscription is one with detailed dates of birth and death. The abbreviated ones give only the date of death and age of the deceased. Sometimes the inscriptions are vague: „Grob Kowalskich” [Tomb of the Kowalskis] or „Jan Kowalski lat 70″ [Jan Kowalski, age 70] and nothing more.

Nasz ukochany mąż, ojciec

[Our beloved husband, father]

Moja nieodżałowana żona

[My late, lamented wife]

Pogrążeni w smutku …

[Immersed in grief]

Sometimes they are accompanied by sentiments borrowed from works of literature, poetry, or the Bible.

And finally an essential for researchers: indexing of graves. My rough estimate is that over three quarters of Polish cemeteries have no indexes. Those that do have indexes are most often large municipal cemeteries. It is easy to recognize such a cem eteiy: the pathways are numbered. Indexes can be accessed in the offices buildings of municipal cemeteries and/or in parish offices. There are sometimes old indexes that include graves no longer existing.

Many graves were destroyed as a result of legal regulations in the 1950s, when a statute was enacted stating that graves neglected, abandoned, and not paid for, according to the rates in effect, were to be eliminated, and the plots were to be reused for new burials. According to the regulation, one could buty the next body in place of the previous one after 20 years had passed. In practice it seems this meant the old plates were removed and the next body was buried on the remnants of the old one.

The descendants of emigrants from more than a century ago have little chance of finding the graves of their great-grand- fathers. If the whole family emigrated, and all that remained were old folks and distant relatives, then in time there would be no one left to care for the graves of ancestors.

The oldest graves in rural and district cemeteries date from the mid-19th century. You do find older ones, mainly those of local landowners and priests. Only their monuments have withstood the test of time.

Poles care a great deal about family graves. The average family visits the cemetery several times a year, usually on anniversaries and before Christmas and Easter. But the most important days to visit are the first and second of November. November 1st is called Dzień Wszystkich Świętych [All Saints’ Day], and the 2nd is Święto Zmarłych [All Souls’ Day] (the so-called Zaduszki). On those days all Poles set out on a journey to the burial places of those nearest and dearest to them. It is a good occasion for meeting potential relatives.

The cemeteries „burst at the seams,” as they say; there are crowds in the pathways, in the parking lots, traffic jams on the highways and access roads, and everywhere police control safe access. Along the fences a multitude of vendors sell flowers and candles, and at the entries are volunteers collecting donations.

The evening of November 1st in Poland would be a delightful sight from a bird’s eye view: darkness all around, but below vast illumination from little colored lights.

These two days show very well how much the memory of the dead and the preservation of Christian tradition means for Poles.

P.S. I have visited hundreds of cem- etries, and every time I enjoy it greatly. Thanks to genealogy, I have come to love cemeteries. There is one that I find the most delightful: the Łyczakowski Cemetery in Lwów. It is not only one of the oldest European necropolises, but also a unique temple of history and art. The delightful monuments of great Poles comprise a valuable collection of sculptures and bas-reliefs done by the finest sculptors and engravers.

I encourage you to take a trip to Lwów.

There are a number of Websites with excellent photos of the cemetery in Lviv/Lwów that Poles call Łyczakowski, or as Ukrainians call it, AunamecbKuu ueunmap [Lychakiuśkyi tsvyntar]. Some of them are:

http://www.lwow.com.pl/lycz.html

http://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cmentarz_%C5%81yczakowski

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lychakivskiy,Cemetery

http://www.lwow.home.pl/lfot.html

Iwona Dakniewicz, Łódź, Poland, e- mail: genealogy@pro.onet.pl

Source: Rodziny, Fall 2007, The Journal of the Polish Genealogical Society of America