Edward Savage painted The Washington Family at Mount Vernon between 1789 and 1796. Young George Washington Parke Custis, standing by his stepgrandfather’s side, appears to be about ten years old; Eleanor Parke Custis, at Martha Washington’s right, is about twelve, just entering her most attractive years . Without detracting from their dignity as President and First Lady, Savage managed to endow George Washington – with an appealing informality that casts a sense of family -warmth over the entire picture.

MELLON COLLECTION , NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, COURTESY Life

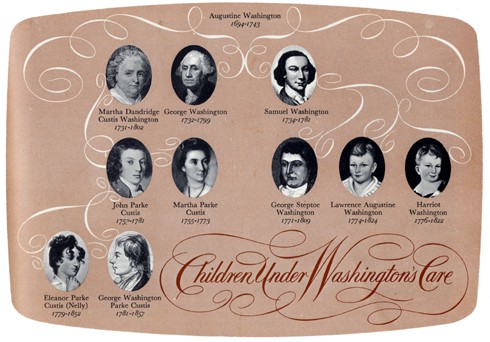

Although he was the Father of our Country, George Washington begat no children of his own. But he knew what children were made of. He came from a large family–his father had ten children by two wives and he outlived them all. Near the end of his life, his home at Mount Vernon became the center of a great clan including eighteen nephews and nieces in varying degrees of dependency upon him. In this home he reared two generations of Custis children, beginning with a boy and girl by Martha’s first husband, the dashing, erratic multimillionaire Daniel Parke Custis. Three children of his brother Samuel also knew George Washington as their immediate guardian. And in the supervision of his estates, he witnessed the intimate affairs many other families, white and black.

From all these, he learned a lot about parenthood. Like most man, he probably thought he learned more than he did. He was supremely confident of his ability to advice his young kin on all kinds of personal matters, . But in a final rating of his talent as a parent, his biographer , Douglas Southall Freeman, concludes he was “a failure”.

Perhaps he was a failure when it came to raising Martha’s children, John (Jackie) Parke Custis and Marth ( Patsy) Parke Custis. These two, although they were both under five when he married their mother in 1759 n never seemed to come under his full command. For one thing, were both much richer than he was, so he had to treat them with a certain respect. After all, it’s hard to spank a millionaire, no matter how small he is.

His wife Martha, wasn’t much better. She was an indulgent, fearful mother —as perhaps young widows tend to be –and she was filled with anxieties over her children’s health. She never liked to leave Jackie alone. She couldn’t bear the worry of having him inoculated for smallpox , so George had to arrange a secret rendezvous with the doctor in Baltimore. She dressed her Jackie in the finest suits from London (with velvet linings), and gave him a liveried body servant to find his hat (laced with silver) and be sure his shoes were buckled properly.

At fourteen —after several years of desultory tutoring in Latin and Greek – Jackie was sent away to boarding school. In a letter to the headmaster, Washington introduced his stepson as „a boy of good genius … untainted in his morals, and of innocent manners.” But he added the hope that the school would be able „to make him fit for more useful purposes than a horse racer.” At that age, Jackie’s only interests were „dogs, horses, and guns.”

Some time later, after the boy’s exploits in and out of school had driven him to despair, the headmaster told Washington exactly what he thought of Master Custis. ” I must confess to you I never did in my life know a youth so exceedingly indolent or so surprisingly voluptuous: one would suppose Nature had intended him for some Asiatic Prince!”

What could Washington do? He couldn’t cut off Jackie’s allowance. Martha wouldn’t let him use a horsewhip. The line of command was too vague to permit a direct order. And besides, Washington rather enjoyed his sporty stepson.

When Jackie decided he’d try a little higher education, Washington took him up to New York City to enroll him in King’s College (Columbia)–accompanied by a body servant and two fine horses (a gray and a bay). He was also able to persuade the faculty to grant his stepson the unique privilege of taking meals with them.

This arrangement lasted until Jackie decided to marry Nelly Calvert (of the Baltimore Calverts), who lived across the Potomac from Mount Vernon. Washington tried to postpone this wedding, but, again, he had no means except suasion, and that wasn’t enough. Jackie soon married Nelly and settled down to a gentleman’s life of dogs, horses, and guns.

When Washington became commander in chief of the Continental Army, Jackie developed a polite interest in the military. He accepted a commission in the local militia but didn’t leave home to do any campaigning. At the end of the war, when the front lines were close by at Yorktown, Jackie rode over to his „Pappa’s” headquarters to serve a spell as a temporary aide-de-camp. There he caught some foul camp disease and died.

His younger sister, Patsy, had died some eight years before, at the age of seventeen. She was a delicate child, subject to convulsions. Martha had tried everything to restore her health, including „fit drops” and baths at Berkley Springs, in what is now West Virginia. Washington did what his wife told him to do but otherwise stood helplessly by as the sad little girl dwindled away.

Jackie was twenty-seven when he died. He left four children: three girls and a boy – and a splendid stallion called Magnolia. The two oldest daughters went with their mother when she remarried. The boy and the other girl stayed with their grandmother at Mount Vernon. Washington took care of the stallion for a while but eventually traded it to Henry Lee for five thousand acres Kentucky land.

In the eyes of the second brace of Custis children, Washington was a famous grandfather rather than a parent. He was too old and too busy with the destinies of republic to spend much time with them. He couldn’t tell bedtime stories or play ball in the front yard. But he enjoyed having „the children” living on his estate. They were an attractive pair- peacock and a bantam rooster.

Eleanor, the older (called Nelly like her mother), was an adorable young lady. She had all the social graces. She played the harpsichord, sang her grandfather’s favorite songs for him, and entertained his distinguished guests. At the age of nineteen, she became engaged to son of Washington’s sister, and, as a special compliment to „Grandpapa,” she chose the twenty-second of February, 1799, for her wedding day. It turned out to be his last birthday.

Eleanor’s little brother, George Washington Parke Custis, called „Young Custis,” was a chip off the elegant and extravagant Jackie. For Washington this young man must have been a trial to the spirit, but again, for some reason, little or no parental discipline applied. Perhaps, like his father, Young Custis was harming and so rich — and so much his grandmother’s boy – that Washington couldn’t lay a hand on him.

Young Custis took the same rosy path as his father. Instead of Columbia, however, he tried Princeton, where straightaway he got into some „contest with the passions.” Washington did not identify this contest specifically, but he spoke broadly of five areas of concern: ribaldry, rioting, swearing, intoxication, and gambling. In describing him to Professor Stanhope Smith of that college, he used wards that might have been used to describe the boy’s father, Jackie. He said Young Custis had an „almost unconquerable disposition to indolence in everything that did not tend to his amusements.”

After this episode Young Custis sent his stepgrandfather a flowery letter of apology and announced that he was transferring to St. John’s College in Annapolis. He lasted there for a few months and then, during the war-scare year of 1798, he volunteered to defend his country against the foe. He asked Washington’s permission to enlist in the local troop of Light Dragoons with the rank of cornet (the man who carried the colors). Permission was granted after an affair with some sixteen-year-old girl was cleared up.

After Washington’s death, Young Custis married a local belle, Miss Mary Lee Fitzhugh, and built a mansion for her on his estate opposite the capital city. He called it Arlington –and later, he gave it to the man who married his only child, an officer in the U.S. Army by the name of Robert E. Lee. This estate is now covered with a fort, a cemetery, and a big building shaped like a pentagon, as well as Arlington House.

Before he died, Young Custis became venerable and honored. He wrote a play called Pocahontas, or the Settlers of Virginia which ran twelve nights in Philadelphia „with great success.” He gave a memorable speech on the night of June 5, 1813, when the people of Washington, D.C., celebrated the news of the Russian victory over Napoleon. He was in frequent demand as a patriotic orator. In his addresses, he always paid tribute to his grandmother’s second husband (whom he called „Pater Patriae”), the noblest of models for his boyhood and for all red-blooded American boys. If he had any criticism of Washington, it was simply that he got up too early in the morning and worked too hard during the day. Also, his clothes lacked style.

Since Washington couldn’t do very much with or about the children and grandchildren of his wife, he tried to exercise more parental authority over the children of his younger brother, Samuel: George Steptoe, Lawrence Augustine, and Harriot. He tried to make these three what the Custis children never could be, namely: plain, hard-working, middle-class citizens.

Samuel’s children were born on a comfortable estate in western Virginia near a large tract of land belonging to Uncle George. Samuel had, successively, five wives, and he died soon after he married the last one–in 1781, the same year Jackie Custis died. For some time thereafter his children lived on with their stepmother, and then, after Uncle George went out to inspect his western lands and relatives, they came east to grow up at Mount Vernon. According to Washington’s diary, Samuel’s estate was „wretchedly managed,” and he felt the children would have a better opportunity under his care. George was then fourteen; Lawrence, eleven; and Harriot, nine.

The first thing he did was put the two boys in a boarding school run by a Presbyterian minister in Georgetown. The girl, Harriot, stayed at Mount Vernon for a while, possibly as a playmate for the Custis children. But she was always a „country cousin,” a poor relative from the sticks of western Virginia.

To be continued.

Reprinted from “AMERICAN HERITAGE” , April 1963