The Decline of the Commonwealth

The arrival of the eighteenth century brought a gradual decline of the Commonwealth. Starting with the so-called Silent Diet, when tzar Peter the First succeeded in imposing Russia as the guarantor of Poland’s internal political system, it is indeed difficult to talk about the country’s sovereignty. All attempts to save the country turned out to be a fiasco due to the narrow-minded ness of the Polish gentry that, in fear lest they lose their „golden freedom,” was ready to sacrifice the state’s independence.

All reform-oriented men and women, who were determined to bring recovery to the country, were treated worse than strangers. The aristocracy and the nobility did not agree to introduce taxes, which would allow maintaining a strong army and an effective administration of the state. Diets were self-adjourned through the application of the principle of liberum veto, a principle that accounted for plunging the country into deep anarchy. Throughout that time it was generally believed that „Poland relies on misgovernment.” The self-complacent gentry tended to believe that the weaker the state was, the safer and more secure they might be since the neighbors were supposed to leave the Polish state alone.

The first attempts to carry out reforms were made by king Stanislas Leszczynski. They ended up in a failure due to the lack of support from the gentry and the aristocracy, and also because of Russia’s intervention.

The man who continued the cause of the reforms was King Stanislas Poniatowski. After ascending the throne in 1764, he was determined to raise the Polish state from its decline. His person is a subject of extreme controversies even today. In the light of recent research and in the opinion of most historians, his work deserves recognition. The King, despite the growing adversities, was extremely consistent about reforming and modernizing the country. During the first years he was prone to believe that the interests of the Commonwealth and those of the neighboring states could be reconciled. His empty hopes were soon to fade away after the first partition of Poland.

The reigning monarch was thus punished for his efforts to abolish the liberum veto during the session of the Diet in 1766. Though he became aware of the hostile approach of the neighboring powers to the idea of the country’s rebirth, he continued in a step-by-step approach through his entire reign to take maximum advantage of all opportunities to force his powerful adversaries to agree to the reforms.

The Confederacy of Bar

The date is February 29, 1768. At the township of Bar, in the province of Podolia, an armed union was established by the gentry against the patronage of Russia and against the re-forms of Stanislas August Poniatowski. The gentry-dominated confederacy, known as the Confederacy of Bar from the name of the township, comprised the opponents of the Czartoryski Family from which king Poniatowski had come. It began as an armed rebellion against the Russian units of the Podolia gentry, gathered around the house of the Potockis.

The confederates were for four years fighting against Russia, the king and the Protestants for the defense of gentry freedom and for the independence of the state. They believed the monarch to be a tool in the hands of Empress Catherine the Second. Theirs was a patriotic movement on the one hand, striving to regain the country’s independence, on the other it was definitely conservative and op-posed to all reforms.

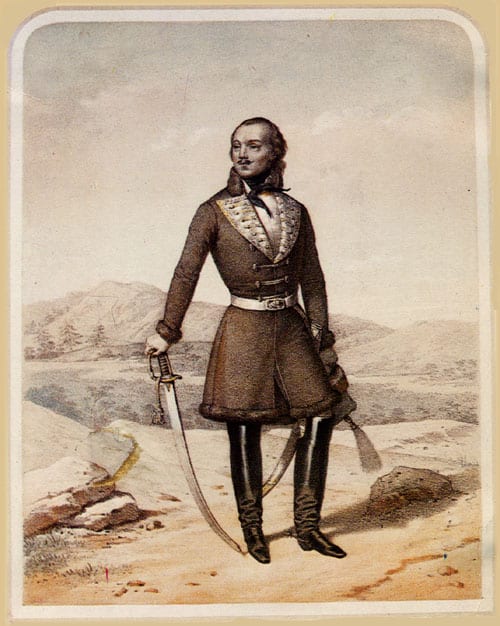

One of the leaders of the union was Kazimierz Pulaski, Marshall of Sieradz and sheriff (starosta) of Zezulaniec. In his youth he received a superficial education and in contrast to Tadeusz Kosciuszko was not genuinely interested in economic, social and political issues. He spent his young years at the court of Courland’s prince Karol and in the company of fellow soldiers. The soldierly craft was his true and only avocation in life.

Pulaski was indeed a true-born cavalry man and personally acquired real experience in numerous fights. He was also a man of generosity and sacrificed the whole of his personal property for the cause of the confederacy. One of his confederate companions Jedrzej Kitowicz, in his memoirs, recalls the figure of his commanding officer in the following way: ” His favored pastimes were at the time free from the enemy to practice hand gun firing, to wrestle with some strong man, and on horseback to practice a variety of exercises, and to play cards all night.”

Confederate camps

In the spring of 1769, the mountains and forests of Beskidy were filled with confederate detachments. In April, Kazimierz Pulaski himself arrived to Gorlice in order to discuss the building of guarded camps in that area. The camps were built in places such as Kobylanka, Izby, Konieczna and Wysowa.

At Kobylanka, renowned for the miracle-making painting of Jesus of Kobylanka, Pulaski met a regiment commanding officer Józef Bierzunski who swore allegiance to the confederates.

At the borderline village of Izby, Adam Parys, marshall of Sandomierz, established a guarded camp which looked like an open entrenchment prepared to fight in defense against an attack coming from the front. It included a deep moat, a wall and a middle place for the artillery. This particular camp played a great role in 1770 through its close proximity to Slovakia’s place of Presov, the headquarters of the confederates. Over time, the nearby castle of Zborov housed the superior authority of the confederates. The camp ceased to function after Austria had declared the area as a sanitary cordon and deployed Austrian troops along the borderline with Poland.

Following Pulaski’s stay in the village of Izby, legends became abundant about his miraculous rescue at places called Swierzowa Ruska and Pilzno, owing to the grace of God’s Mother of Izby. As late as 1851, the local orthodox church had at its top section a painting showing the camp commanding officer praying before the figure of the Mother of God. At a later time the painting was allegedly covered with yet another painting. There were more legends and stories showing the confederates as oppressors of the people. It is a fact that Radziwill’s militia units, commanded by captain Szyc and stationed at Regetów, were ruthlessly dealing with the local population of Lemkis. In addition, the stationing of the military units caused the poor region to suffer from hunger. However, the local population was still enlisting under the banners of the confederates. This is shown in Pulaski’s letter to prince Michael Lubomirski in which the former says that „. . . a large number of the peasants were reporting to the army, declaring themselves ready to come to the camp . . .”

The entrenchments raised by the confederates were preserved in a fairly good condition until World War II. The German troops destroyed them only in part. The destruction was completed by bulldozers in the land reclaiming project of 1985.

There was also a large confederate camp overlooking the village of Konieczna. The camp was commanded by Józef Miaczynski. Marshall of Belz. Kazimierz Pulaski used to stay there quite often. The proclamations made out on the Slovak side were countersigned at Konieczna to give them the force of law. It was there that, among other things, the act of the interregnum was proclaimed. By this token, the village was elevated to the rank of the confederate capital. The year of 1770 saw battles there fought by the Polish units against the Russian forces commanded by Yeltcheninov and prince Shakhovskiy. The latter seized the village and the entrenchment on August 3, 1770.

The village of Wysowa, now a well-known resort, had entrenchments raised on the north-eastern slope of Mount Czerszla. The en-trenchment dominated over the pass of Wysowa which was of strategic importance.

The book called 'Geography or the exact description of the kingdoms of Galician and Latimeria” (published 1858) gave the following description of this place: „This village is known for its borderline posts, customs from the side of Hungary and for the Polish confederate camps from 1769 to 1772, where there were frequent skirmishes with Russian troops, as much as for the outlying Russian borderline villages from the side of Hungry.”

At the place called Zdynia, there was no camp, military units were stationed there in the years from 1769 to 1770, often causing hunger for the local villages. The Russian troops of prince Shakhovskiy often made incursions into that place.

Battles with Russian troops

It was from Beskidy that the Marshall of Sieradz set out with his cavalry unit on long-range missions to reach Lithuania, Lwów, Pilzno and Cracow. The raids were continued from the spring of 1769 to August 1770.

The Russian commanders were pretty much aware that the capture of the camps could deal a decisive blow to the confederates. So, the army was dispatched under the command of general Drevitch in that direction and to force the defenders to retreat from their positions.

Pulaski undertook counteroffensive actions against them in March 1770. At that time other Russian troops with colonel Yeltchaninov were dispatched from the town of Przemyol with the aim of surrounding and seizing the camp of Izby. To prevent this from happening, Pulaski came to Gorlice in April and with his staff officers made plans to counterattack.

Towards the approaching Russians a unit was dispatched with Ignacy Kirkor in charge. A major battle followed at the village of Biecz. The Russian troops were defeated, losing 50 soldiers and officers. In spite of the victory, Kirkor retreated to Gorlice in fear lest there may be more enemy forces and artillery coming that way. In revenge, General Drevitch’s Russian troops sacked the township.

In an attempt to get ready for a general battle with Yeltcheninov’s troops, the leader of the confederates left Gorlice to move to Izby to prepare the latter for defense.

Honorable Pulaski, arrive soon . . .

Without your care, heroic Sir,

In our camp, things’ll go out of tune . . .

– so ran one of the confederate songs.

The enemy force seized Gorlice, but then they were made to leave the township by lieutenant Grabski’s unit and to march toward the camp of Konieczna. Pulaski rushed to the aid of the besieged at the head of Slowoszewski’s hussar regiment and Kirkor’s division. April 12 saw a heavy battle culminating in the Polish victory. 300 Russians were killed or injured and 211 troops were taken as prisoners of war. Thus, the Russian force retreated again to regroup.

At the beginning of May, Yeltchaninov again marched against the confederate force and in the first days of August General Drevitch’s group, with artillery units, approached the area from the north along the Ropa river valley. The Poles concentrated their forces, numbering 2,000 troops, at the camp of Izby. At the beginning of August, the first battles were fought in the foregrounds of Izby and Wysowa where the Polish units defended strongly. In this situation, the Russian general resorted to the tactics of deceit. In secret he came into contact with an Austrian commander stationed along the border, to the rear of the Polish force. The Austrian commander was bribed into withdrawing his units. Giving the appearance of an attack from the front, the Russians under the cover of night moved their forces to the Austrian territory and attacked the Poles from the rear. The Confederates were not prepared to deal with the Austrian betrayal and were forced to withdraw. 113 killed and 14 injured companions were left on the battle field.

The Polish Confederates never came back to the camp which the Russians destroyed completely. Under these conditions, Pulaski left the Gorlice area for ever and moved to the Nowy Targ and Sacz territory. At Krynica, along the Roma pass, he fought a battle against the Austrian hussars. Thereafter, the local mount was named as the mount of Hussars.

In July 1999, the population of Krynica was alarmed by the news that the town authority was planning to move the mound dedicated to Pulaski, unveiled in 1929 to mark the 150th aniversary of the death of the hero of the two continents, to another area closer to the Confederate entrenchments of Tylicz. The reason for this decision was the change of an owner. of the site. The mound was Poland’s first monument dedicated to Pulaski and the third of its kind in the world – after those of Savannah and Washington. The cost of the mound was paid for by donations from spa visitors, holiday makers and the population of Krynica.. However, the issue died out after many interventions.

The dedication and sacrifice of the Confederates turned out to be in vain. When Kazimierz Pulaski defended Czestochowa, on August 5, 1772, Russia, Austria and Prussia signed the treaty of partition. The Austrian army immediately took control of the Gorlice area and on September 11 Empress Maria Theresa legalized the conquest by means of a proclamation. The region was called Galicia and Lodomeria, and Gorlice was included within the borders of what was called Western Galicia.

Yet until today, in the southern part of Poland, the memory is still alive of Kazimierz Pulaski, the leader of the Confederacy of Bar, and of his cavalry raids. It is appropriate therefore to recall the words of the poet Slowacki from his poetical drama „Beniowski”:

From the land where salt lakes shine

To the land where amber pieces are mined

The ranks enamored of fame, fraternal,

Carried our last banners.