The baseball park that would bear the name of Charles Comiskey was scheduled to open July 1, 1910. Comiskey envisioned a park where the common man could be assured a seat as good as an alderman or an opera singer. His choice of location was neither coincidental nor haphazard. In 1890 he had played first base for the Chicago Pirates of the Brotherhood in a small enclosed grandstand directly east of the new park. Yet Comiskey based his decision to build at 35th Street and Shields Avenue more on what he viewed as sound business considerations than on personal sentiment. Besides its convenience to the Wentworth Avenue streetcar line, Comiskey felt that the ballpark would in time become the focal point of community life among his own people—the ethnic Irish of Bridgeport, Canaryville, Washington Park, and Back of the Yards.

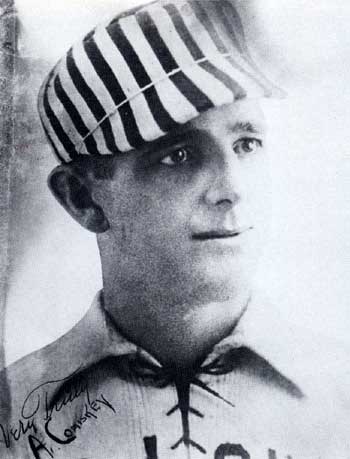

Chicago Pirate first baseman Charles Comiskey would become a revered civic magnate and build a baseball monument in his own name. CHS, lCHi-21148.

Today, Comiskey Park has lost its traditional demographic base of support and is slated for the wrecking ball in 1991 when the new White Sox park is completed. It might have survived into the twenty-first century had Comiskey chosen to heed the advice of the young architect entrusted to build it. Instead, he allowed cost considerations to stand in the way of structural and architectural innovation, resulting in a triumph of mediocrity over genius. By the 1980s the owners of the White Sox found themselves saddled with an archaic baseball dinosaur that had been sadly neglected in the intervening years. The controversy surrounding the park’s demolition raises questions about what constitutes a landmark. However, the significance of Comiskey Park lies not in its durability or in its style but in the history and nostalgia it evokes.

Charles Comiskey—called the „Old Roman” after helping to found the American League in 1900—was one of the most revered public figures in Chicago by 1910. As a prominent member of the Woodland Bards, a private club of show people, newsmen, politicians, and civic leaders, Comiskey cavorted and entertained his way into the ranks of Chicago’s elite and powerful. While well known for his lavish and extravagant forays, Comiskey required his ball players to pay for the cleaning and pressing their own uniforms. His professional penury was not public knowledge in 1910, for he was admired as a resourceful baseball magnate who had upstaged the Chicago Cubs, his powerful National League rival, with a daring brand of baseball. In 1906 the White Sox—known as the „Hitless Wonders” for their uncanny ability to win ball games despite having a team batting average of only .230, the worst in the American League—defied what seemed to be insurmountable odds by capturing the only all-Chicago World Series, four games to two.

The wooden South Side Grounds, where the White Sox played from 1900 to 1910, was a potential firetrap. CHS, SDN,S858.

Before 1910 the White Sox played in a cramped, single-decked wooden firetrap near the corner of 39th Street and Wentworth Avenue. Known as the South Side Grounds, the park was unsuitable for baseball—or any other athletic contest—when Comiskey arrived on the scene in 1900. The South Side Grounds had been home to the Chicago Wanderers Cricket Club since the 1893 World’s Fair. Abandoned for a year or two and strewn with weeds and garbage, Comiskey leased the grounds and secured loans from the First National Bank to build a new grandstand. During the winter of 1899-1900 construction crews worked double shifts to ready the park by opening day. But even after the costly renovation the size of the South Side Grounds proved inadequate for White Sox fans, who had trouble securing tickets for games. The grandstand was enlarged in 1902, and an overhanging deck was installed in left field for the comfort of bleacher patrons, but in its heyday, total seating capacity never exceeded 7,500.

The Old Roman promised White Sox fans that a modern steel and concrete facility would be erected. As early as 1903 Comiskey scouted the city for a new stadium location. He secured an option on a tract of West Side real estate bounded by Harrison and Loomis streets, Congress Parkway, and Throop Street. Because the Cubs played in a nearby stadium at Lincoln Avenue and Taylor Street, and the surrounding neighborhood was populated by eastern European immigrants who were unfamiliar with and unenthusiastic about baseball, Comiskey reconsidered. He negotiated for several years with the heirs of Mayor John Wentworth to buy the grounds of Brotherhood Park at 35th Street and Wentworth Avenue, the property he considered ideal. But he wouldn’t be able to secure the land for several more years. And so, the White Sox owner purchased the vacant lot at 35th Street and Shields Avenue three days before Christmas, 1908. Comiskey paid Roxanna A. Bowen and her husband $100,000 (with a promise to pay the 1907 back taxes) for property that South Side residents used as a community dumping ground. Years later White Sox shortstop Luke Appling allegedly tripped over a rusty kettle drum that had resurfaced in the middle of the Comiskey Park infield.

Comiskey seems to have looked past the emerging Black Belt already taking shape east of Cottage Grove Avenue. The South Side between 22nd and 39th streets was an area in transition. East of the park from Wentworth Avenue to State Street stood a number of two- and three-story walk-ups built as low-cost housing in the 1870s and 1880s. These structures featured small shops on the ground level and narrow, cramped second-floor apartments appealing to poor, transient families. Though Comiskey did not realize it at the time, the South Side Irish community he hoped to serve was being replaced by an expanding black population.

The energetic Sox owner pressed ahead with plans for his new ballpark, the fifth baseball stadium to be erected on the South Side since 1874. It was to be the third concrete and steel stadium in America. Philadelphia’s Shibe Park was the first in 1909, followed in the same year by Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Concrete and steel structures all but eliminated the threat of fire that had plagued many nineteenth-century stadiums. Safety dictated that Comiskey shell out the money for a modern ballpark. (By 1911 he had leased the old South Side Grounds to John Schorling, owner of the American Giants, a Negro League team managed by the legendary Rube Foster.)

Comiskey envisioned a new home for the White Sox that had spacious contours and an abundance of 25-cent seats in the outfield pavilions. He commissioned thirty-eight-year-old architect Zachary Taylor Davis to design a structure that would favor pitchers and fielders—the „Hitless Wonder” baseball the White Sox were known for. Born in Aurora, Illinois, and educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Davis worked as the supervising architect for Armour and Company. The first major commission of his distinguished career, his design for Comiskey Park established him as the foremost expert on the new and innovative kite-shaped ballpark. Before he began his preliminary sketch, he sent Karl Vitzhum, an architect on Daniel Burnham’s staff, on a tour of other baseball stadiums. Accompanied by Ed Walsh, the most notable White Sox pitcher to date, Vitzhum gathered data and submitted a report to Comiskey and Davis. Walsh’s role remains somewhat of a mystery. Certainly the crafty spitballer was the best pitcher of his day and was a personal favorite of the Old Roman, but it is unlikely that a ball player be allowed to dictate the architectural specifications of his preference.

Source:

CHICAGO HISTORY

The Magazine of The Chicago Historical Society

Summer 1989,Volume XVIII, Number2