The general was supposedly shot with two bullets the moment his plane started running on the airport lane. What happened to the rest of the passengers was unknown. If they weren’t shot, they might have died from an explosion. The bomb exploded probably after the plane alighted on the water [5, p. 209]. The purpose of the explosion was, besides killing the witnesses, to get rid of any traces and evidence and disguise the murder attempt as an accident. Most probably, there was a man aboard the plane, whom Ludwik Łubieński introduced to Sikorski as Jan Gralewski. He might have let a few assassins in, whom he didn’t necessarily have to know personally. It might have been the two assassins mentioned by Philby in a conversation with Heinrich Miiller.

In 1944 in Moscow, during a meeting with Milovan Djilas, Stalin presented his version of events that led to Gen. Sikorski’s assassination. He cynically blamed the British and said they bore full responsibility for the General’s death. In his book, Djilas wrote that Stalin underscored several times that they ought to beware of English duplicity: „They were the ones who killed Gen. Sikorski in a plane and then neatly shot down the plane – no proof, no witnesses” [1, p.73].

Tadeusz Kisielewski believes that Gen. Władysław Anders or his entourage was preparing a coup d’etat against Sikorski, which was never finalized. It should be mentioned that Colonel Leopold Okulicki was then the commander of the 7th Infantry Division. Jan M. Ciechanowski, in his polemic to Norman Davies’ book about the Warsaw Uprising, reveals that Colonel Okulicki, as the commandant of ZWZ (Związek Walki Zbrojnej – an organization within Polish underground armed forces), the Soviet occupation section, was arrested by the NKVD in Lvov on the night of January 21 – 22,1941.

Tortured, he broke during the interrogation. „He gave a wide and detailed deposition regarding activity, structures and management of the whole Polish underground army, and declared his readiness to start a close and wide political and military cooperation with the Soviet government and NKVD” [2, p. 101]. It should be stressed that Colonel Okulicki broke all the rules of the military conduct, and as a soldier he broke the oath of faith to the Republic of Poland, and he deprived himself the moral qualifications one needs to be a commander.

Tadeusz Kisielewski suspects that: „Sikorski’s journey to the Near East which started on May 25, 1943, aimed to not only inspect the Second Corps and to pacify Anders’ 'rebellion’, but also to set up a confident contact with the Kremlin” [5, p. 122]. It was very likely to happen; Stanisław Strumph-Wojtkiewicz also mentions the story in his book [15, p. 67-68].

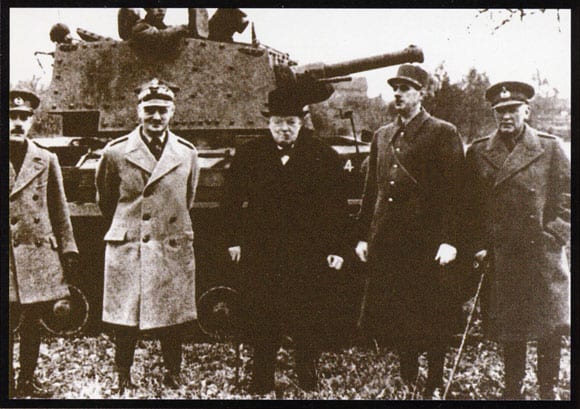

Courtesy of the Polish Military Museum in Warsaw:

September 20, 1941: Prime Minister Winston Churchill and General Sikorski, accompanied by General de Gaulle visit the 10th Armoured Cavalary Brigade.

As Zbigniew Stańczyk recalls, first rumor that it were Poles who stood behind the assassination of Gen. Sikorski appeared the day after the catastrophe on a cabinet meeting [14]. During the meeting it was decided that an interrogative commission would be sent to the Gibraltar base. The commission was instructed to find the body of the general, to localize missing mail, to determine the causes of the accident, and to check ,,if a Polish sabotage was possible”. Sta-nislaw Mikolajczyk vetoed then that too many members of the commission were connected with the 2 Department of the Polish Army Headquarters and that would not be helpful in the search for truth.

MieczysJaw Pruszynski wrote that just before Gen. Sikorski died, he ordered to arrest air force officers suspected of plotting against him. According to Pruszyński, the British were afraid that the Polish interrogation would reveal their system of double agents [11, p.139]. It might have been one of the additional reasons to get rid of Sikorski.

It is seems to be very possible that Soviet Russia was the direct or indirect force standing behind the murder as a country the most interested in the removal of Wladyslaw Sikorski. According to Tadeusz Kisielewski, Soviet special services might have prepared such action using their own or other people. In his opinion, Poles might have been the assassins ,,aware or not that they followed orders from Kremlin” [5, p. 133]. They might have believed that „they executed the will of the Polish antagonists of Sikorski” or they could be agents, maybe recruited among officers the Polish Army. It could have also been British assuming they fallowed the orders of their own government.

Courtesy of the Polish Military Museum in Warsaw:

Chicago, December 18, 1942; Gen. Sikorski in the office of Mayor E. J. Kelly. L-R: Karol Ripa, L. Walkowicz, Gen.Sikorski, Amb. Ciechanowski, Mayor Kelly; in the background: Pilot Główczyński.

But according to the chief of Gestapo Heinrich Miiller, Harold ,,Kim” Philby informed him that the list of passengers of Maisky’s airplane included names of two professional assassins. It doesn’t seem very likely that any Poles could be traveling with Maisky to Gibraltar. Some documents indicate the fact that an assassination attempt on Sikorski was planned by Polish officers. Most of those files are still secret, but even those very few already disclosed are very interesting. According to Eugenia Maresch among those documents are reports of major Howarth, a SOE (Special Operations Executive) special agent in Cairo, to the central in London, dating from February 1943 [7].

They regard the assassination attempt planned on Sikorski by Polish officers. The fact that such documents existed was overly covered up. Any suspicions against the Polish military circuit that was claimed by the MI3 intelligence working in the Middle East were treated in a similar way.

Maria Nurowska in the biographic novel about Krystyna Skarbek, a SOE agent who was using the name of Christine Granville, noticed that Patrick Howarth felt affection toward the hero of her novel [10, p. 175]. Howarth, an Oxford graduate, came to Cairo in summer of 1942 to take the position of SOE officer responsible for technical equipment of agents who were dropped from planes or transported by submarines. He was fascinated by Christine Granville and in his book about SOE agents he puts her in focus a lot [4, p. 35-58]. Madeleine Masson, the author of a biography of Christine Granville, published in her book a poem by Patrick Howarth that he dedicated to the beautiful Pole [8, p. 251]. Christine Granville stayed in Cairo from 1941 to 1943. During that time she had the freedom to contact Polish officers, including those from the Gen. Anders’ Second Corps.

Eugenia Maresch asks if ignoring these signals was a sign of recklessness, or if the British just didn’t want to know about the planned murder, or maybe it was in their interest to drastically remove Sikor-ski from his position of prime minister. As some of British documents state, the idea of the removal of Sikorski appeared for the first time in 1941.

Kazimierz Leski, in his book ,,Życie niewłściwie urozmaicone. Wspomnienia oficera wywiadu

i kontrwywiadu AK” (A life improperly varied. Memories of a Polish Home Army espionage and counterespionage officer), mentioned the cooperation of Krystyna Skarbek with Stefan Witkowski, chief of a secret intelligence organization, ,,Musketeers” [6, p. 124]. Stefan Witkowski introduced Krystyna Skarbek to Kazimierz Leski as a special British intelligence messenger. Besides contacts with the British intelligence service, Witkowski cooperated also with German intelligence and the Committee of White Russians. According to Gen. Klemens Rud-nicki, by the end of 1941, three „emissaries” sent by Stefan Witkowski came to the camp of the Polish Army of Gen. Anders in the Soviet Union with documents highly embarrassing to the Poles [12, p. 167-169]. Those documents were most probably read by Soviet officers and the whole thing might have been a political provocation. According to Kazimierz Leski, Stefan Witkowski, after Gen. Stefan Grot-Rowecki approved his death sentence given by the military court for betraying the Polish government, was shot in September 1942 in Warsaw by Kripo policemen in the service of ZWZ [6, p. 132].

Kazimierz Leski met Stefan Witkowski for the first time in the fall of 1939 in the apartment of countess Teresa Lubienska in Warsaw, and in the beginning he cooperated with him in the organization ,,Musketeers” [6, p. 72]. Similar to Kazimierz Leski, Józef Garliński, future Polish historian-in-exile, was also connected with the ,,Musketeers”. We should mention here that according to Garlinski, Gen. Sikorski drowned after his plane’s catastrophe [3, p. 121].

The destiny of Christine Granville and Countess Teresa Lubienska was very tragic. After the war, in 1947 in Cairo, Edward Howe, an old friend of Christine, gave her Ian Fleming’s address [9, p. 143]. Edward Howe believed that the famed author would be interested in the personage of Christine and maybe help her in finding a job.

In the years 1940 and 1941, Fleming was involved in a plot that led to the unfortunate trip of Rudolf Hess to Scotland. Hess flew to Scotland on May 10,1941 and was arrested there.

Fleming’s persona could have definitely interested: Christine Granville. Ian Fleming was seeing her occasionally, as she worked then as a stewardess on a cruise ship.

Christine kept her meetings with Fleming secret. One of the places they met was the hotel Granville, near Dover. Obviously those meetings entertained them both. After a weekend with Ian Fleming, Christine told her friend that for the first time since the end of war she spent some „magical hours” with someone whose company was extremely pleasant for her [9, p. 144].

In January and February of 1952 Fleming wrote the novella „Casino Royale”, which was published no earlier than April 1953. Donald McCormick, Fleming’s biographer, believes that Christine Granville was the prototype for Vesper Lynd, the main female character. In chapter XXVI James Bond talks with Vesper about marriage. In the following chapter she’s already dead, leaving a letter to Bond, in which she admits to James that she was a double agent, working for the Russians as well as the British. In the last paragraph of the book, in a telephone conversation, Bond says: ,,Pass this on at once. 3030 was a double, working for Redland…. The bitch is dead now” [9, p. 153]. Daniel Farson, another author fascinated with Christine Granville, was referring to that when posting a question if she was a double agent [9, p. 148].

On June 15,1952, before „Casino Royale” was published, in the hall of the Shellbourne Hotel, located by Le-xham Gardens in Kensington, London, George Muldowney stabbed Christine Granville.

The questions appear: Could Ian Fleming predict Christine’s death? What does Vesper Lynd’s death mean? It seems that Donald McCormick answered these questions. He wrote: „Christine Granville not only knew about Sikorski’s death but something of the background to it and events connected with it, leading to the conclusion that he was murdered” [9, p. 149]. So Krystyna Skarbek was another victim – she knew too much.

On Friday, September 12, 1952, in London, the Polish newspaper, „Dziennik Polski”, wrote:

„An Irishman [George Muldowney] with a face of a half-educated person murdered Krystyna Skarbek, a hero, who helped the Allies’ cause so much, who was awarded with so many foreign medals and whose achievements during the war became almost a legend. No identity check, no formalities. A few concise sentences and the judge is ready, putting on his black cap, he reads the death sentence. Everything happens fast, three minutes at the most” [10, p. 255]. We should add that the killer was mentally unstable and he refused the assistance of a public defender. The sentence was announced on September 10 and the murderer executed on September 30.

One of the closest friends of Krystyna Skarbek, attending her funeral at the Roman-Catholic cemetery in Kensal Green, in London, was Countess Teresa Łubieńska.

A few years later she met the same fate. She was stabbed on May 24, 1957, at a subway stop by Gloucester Road. The death of the countess is a mystery to this day. In his book dedicated to the soldiers of World War II, Cardinal Francis Spellman recollects the words of the Archbishop of Edinburgh and his opinion about the Allies’ responsibility for Poland, spoken on the 5th anniversary of Poland’s takeover by the Soviet Union and Germany, and a year after General Sikorski’s death, with Poland facing once again the threat of liquidation – this time by the Soviet Union. Archbishop MacDonald stated then that: „The honor, the pride and cherished treasure of every English heart will be ruthlessly flung on the scrap-heap if Poland is not free, […] We may conceal the truth from ourselves today, we may camouflage the facts and comfort ourselves with deceitful, soft-sounding words now, but one thing is certain: those guilty of the crime of liquidating Poland, if it comes to pass, will be scorned and despised by future generations; they will justly be regarded with horror for all time, as seared with the brand of Cain in the murder of a faithful ally and brother-nation in arms” [13, p. 67].

Selected bibliography:

1. Djilas, Milovan, Conversations with Stalin, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York 1962.

2. Ciechanowski, Jan M., Zmarnowana szansa (Uwagi i refleksje nadpolskim wydaniem książki Normana Daviesa ,,Powstanie ’44”, ,,Zeszyty Historyczne” nr 149, p. 99-117, Paryż 2004.

3. Garliński, Józef, Poland, SOE and the Allies, George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London 1969.

4. Howarth, Patrick, Undercover, The Men and Women of Special Operations Executive, Routledge & Kegan Poul, London, Boston and Henley, 1980.

5. Kisielewski, Tadeusz A., Zamach, Tropem zabójców generała Sikorskiego, Dom Wydawniczy REBIS, Poznań 2005.

6. Leski, Kazimierz, Życie niewłaściwie urozmaicone, Wspomnienia oficera wywiadu i kontrwywiadu AK, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa 1989.

7. Maresch, Eugenia, Katastrofa w Gibraltarze. Po 60 latach wciąż

tajemnica, „Mówią Wieki” 2003, nr 7.

8. Masson, Madeleine, Christine: A Search for Christine Granville,

Hamish Hamilton, London 1975.

9. McCormick, Donald, 17F: The Life of Ian Fleming, Peter Owen

Publishers, London 1993.

10. Nurowska, Maria, Miłośnica, Wyd. WAB, Warszawa 2001.

11. Pruszyński, Mieczysław, Komu mogło zależeć na śmierci gen. Si-

korskiego, „Przegląd Wojskowo-Historyczny” 2 (2001), 3, p.136-140.

12. Rudnicki, Klemens, Na polskim szlaku, Wspomnienia z lat 1939

– 1947, Polska Fundacja Kulturalna, Londyn 1984.

13. Spellman, Francis Joseph, No Greater Love: The Story of Our

Soldiers, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1945.

14. Stańczyk, Zbigniew L., Jeśli był spisek.,.., „Rzeczypospolita”

z 4.07.1998 („Plus – Minus”).

15. Strumph-Wojtkiewicz, Stanisław, Sikorski i jego żołnierze, Księgarnia Ludowa T. Lemański, Łódź 1946.

Part I