Many people also know that the „ORD” designation on their luggage stands for Orchard Field, the tiny airfield that once stood on the 0’Hare site. But few anything about the quiet young man after 0′Hare Airport is named. City Hall will tell you that he was „a Chicago air hero”, but that answer is only partially correct. Edward Henry “Buttch” 0’Hare, Chicago’s honored World War II pilot, was actually a St. Louisan with few ties to Chicago.

O’Hare’s early life was unremarkable. He was born in the River City on March 13, 1914, one of three children of Edward J. 0’Hare, the owner of struggling trucking company. His first sixteen years were spent near his birthplace, an old brick storefront at 18th and Sidney streets in a non-descript working-class south St. Louis neighborhood. A shy boy, often picked on by bullies, he became an excellent swimmer and a crack rifle shot.

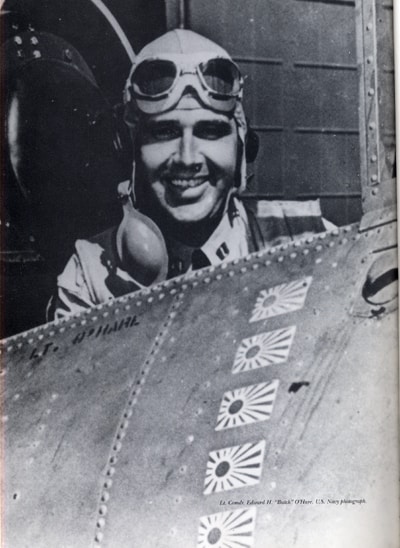

Lt. Comdr. Edward H. “l” O’Hare. U.S. Navy photograph.

The life of young 0’Hare began to change dramatically during his early teens. While still maintaining his partnership in the Dyer & Hauling Company, 0’Hare’s father began a career as a lawyer, but his successful defense of Louis, Illinois, speakeasy owners gave a slight taint to his practice. „E. J.,” as he was known, also became involved in a dog racing tack in Madison County, Illinois, and he eventually bought the patent rights to the mechanical rabbit that the dogs chased. In 1924 he was indicted in connection with a scheme to withdraw medicinal whiskey from bonded warehouses. The charges were later dropped. The turning point in the family fortunes came in 1928 when Chicago’s organized crime czar Al Capone, realizing that the lucrative profits from Prohibition might not last forever, decided to muscle into professional sports. He offered E. J. 0’Hare a job as manager of the Hawthorne Dog Track in suburban Chicago. The move meant great wealth for E. J. 0’Hare, but it cost him his family. His wife, Selma, and his children remained in St. Louis. In 1932 the couple divorced.

At age sixteen, perhaps to escape the family turmoil, young Edward 0’Hare entered the Western Military Academy at Alton, Illinois. He excelled in everything, and after graduation in 1933, Rep. John J. Cochran of Missouri’s Eleventh District sponsored his appointment to the United States Naval Academy. There he won the nickname „Butch!’ He graduated in 1937 and was assigned to the USS New Mexico. In June of 1939 he realized his dream of becoming a pilot when he reported to the naval air station at Pensacola, Florida, for his year of training.

Even the relative isolation of the military could not protect young 0’Hare from the controversy that still surrounded his father. On November 8, 1939, E. J. left Sportsman’s Park, which he had headed since 1932, and drove down Ogden Avenue toward the Loop. As he approached the intersection at Rockwell Avenue, an expensive coupe (similar to his own) pulled up alongside, and guns began blasting. 0’Hare’s vehicle raced out of control for another block before smashing into a utility pole. A gun, a crucifix, a rosary, a religious medallion, and several phone messages were found on the front seat next to 0’Hare’s body. The killing, of course, made headlines, and reporters competed with the police to uncover leads.

The disclosures of the next few weeks revealed a tale of underworld crime and of the secret triple life that E. J. 0’Hare had been leading for eight years. In his first role 0’Hare was a key member of the Capone mob and one of its top financial wizards. He had developed a wide network of political contacts, including a business partnership with municipal court judge Eugene Holland, who dismissed 12,634 gambling charges and convicted only twenty-eight gamblers over several years. 0’Hare had expanded Capone racing interests in Massachusetts and Florida, and when Capone went behind bars in May of 1932, ownership of the mob’s racing interests was transferred to 0’Hare and partner John Patton. As the young mayor of Burnham, Illinois, Patton turned the town into a vice village and later became Capone vice lord for Cicero and Stickney as well. E.J. was also found to have purchased stock in the Chicago Cardinals, an indication, perhaps, of mob’s plans to infiltrate professional football.

With an expensive house in Glencoe and extensive real estate holdings, E. J. 0’Hare preferred to be known in his second role, that of a “wealthy clubman.” Whereas most members of the Capone hierarchy were easily recognized by the public, 0’Hare remained completely detatched from the reputation of his boss. In fact, he went out of his way to condemn organized crime. Newspapers frequently reported his verbal attacks on „unsavory hoodlums” and noted his orders that criminals keep away from his race-tracks. If 0’Hare profited from his mob ties, he refused to become part of its social life.

E. J. 0’Hare’s most important role, however, proved to be that of government informant. In the weeks following his death, reporters uncovered a fascinating story that had begun in the early 1930s. A rekindling of the friendship between E. J. and newsman and former St. Louis friend John Rogers led to contact with federal investigator Frank J. Wilson, who was determined to put Capone behind bars. Why 0’Hare turned informant may never be known. He might have been motivated by impending investigations of his own income taxes. Perhaps O’Hare agreed with some mobsters who thought that Capone’s reputation and violent tactics hurt the money-making potential of the rackets.

O’Hare may have wanted to cooperate in order to insure that his son would not be denied admissions to Annapolis because of his shady business dealings. Whatever the reason, E. J. supplied critical evidence against Capone. When Capone finally learned the identity of his betrayer in 1937, cellmates at Alcatraz heard him vow to 0’Hare killed. Upon being released, the ex-convicts informed E. J. of Capone’s threats, and he spent the last two years of his life in semiseclusion. His execution was probably delayed because his business talents were too useful to waste. In November 1939 0’Hare reportedly refused to contribute $50,000 to a welcome home fund for Capone. It was thus more than coincidence that 0’Hare’s murder came only a few days before Capone’s release from prison. The press speculated that the mob, fearing Capone’s wrath, finally carried out his order. A phone message bearing an FBI number found on 0’Hare’s body was further evidence of his role as an informer; he was to leave for Washington the following day.

At the time of his trial in the early 1930s, Al Capone(center) had not yet learned that mob member E.J. O’Hare had supplied criminal evidence against him. In prison, Capone vowed to have O’Hare killed. CHS, DN 97, 061.

E. J. 0’Hare’s funeral at the St. Louis church that the family had attended for decades drew a curious mixture of Capone henchmen, federal agents, Chicago police, and newsmen from across the country. Butch 0’Hare, after being questioned by Chicago authorities, was no doubt anxious to return to the anonymity of the navy. In the summer of 1940 he qualified as a naval aviator, and that July he was assigned to a squad- ron on an aircraft carrier. He married St. Louisan Rita Wooster on September 6, 1941, the couple moved to San Diego, where he stationed.

To be continued.

Source:

CHICAGO HISTORY

The Magazine of the Chicago Historical Society

Fall and Winter 1988- 89

Volume XVII, Number 3 and 4