Lucja Swiatkowski Cannon

ORIGINAL VERSION OF BOOK REVIEW

Halik Kochanski’s The Eagle Unbowed presents for the first time Poland’s unique experience of World War II, different from any other country because it was the only one invaded by both Germany and theSoviet Union at the same time in 1939. Polish people suffered the harshest occupation policies, witnessing genocide, experiencing deportations, executions and starvation, yet never had a quisling government. Poland was the only country occupied by foreign armies from the first day of the war to the last and the only Allied country left behind the Iron Curtain. Presentation of Stalin as Uncle Joe in the West prevented recognition of Soviet persecution of Polish people not only during the war but long into the Cold War, including Western cover-up of the Katyn Massacre. True war history of Poland is largely unknown in the West but opening of the archives and ending the outright falsifications of the communist era allowed a fresh, comprehensive look at Poland’s experience. Kochanski’s examination of this experience alters the perception of the war and challenges long-held assumptions.

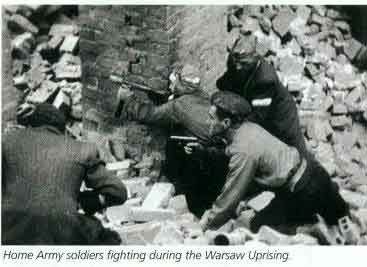

Poland mounted the greatest military effort on the side of the Allies, after the Big Three, and fought on virtually all fronts in Europe and North Africa. Poland fielded four different armies. The first army comprised remnants of the defeated Polish Army who managed to escape to the West and fought in France and Britain. The second Polish Army was made up of Polish exiles, deported to the Gulag in 1940-41 by the Soviet Union where half perished. Survivors were released after the German invasion when the Soviet Union aligned itself with the West. This Army fought in the Italian campaign, most famously at Monte Cassino. The third Polish Army was also made up of Polish exiles and prisoners in the Soviet Union who did not make it out with the Second Army. They fought as part of the Soviet Army on the Eastern Front. And the fourth Polish Army, which was the Home Army in occupied Poland itself, was the largest resistance movement in Europe. It was not only a guerilla force, but had a parallel underground government that incorporated a civilian administration, which performed many of its functions under foreign occupation and maintained readiness to take over at the moment of liberation.

Poland made a significant contribution to the Allied victory in the war. Aside from direct military manpower, Poland contributed vast amounts of vital intelligence. The Polish government gave the British and the French first copies of Enigma, the German military coding machine, and the key to decoding its messages. Later, the Poles supplied the original V2 rocket and its full documentation, thus neutralizing the most important German advantages. Throughout the war, the Home Army was providing comprehensive intelligence on the German Army as it struggled on the Eastern Front.

This fresh look at the Soviet killings and Siberian exile of Polish elite where half perished and the dark years of the German occupation and Holocaust counters the image of” the good war,” prevalent in the West, where exemplary defeat of evil Hitler was followed by peace and democracy. As Kochanski’s vivid descriptions of war against the Polish people demonstrate, both Germany and the Soviet Union were engaged in terror against the population of occupied Poland. And this terror did not stop with the end of the war but continued to break down the resistance to the imposition of a totalitarian system.

Kochanski discusses the Holocaust within the context of German policy in Poland and the unexamined Polish experience of the war in order to clarify Western misconceptions. She emphasizes shock and disbelief of both Jews and Poles, and later Westerners, at the fast-moving German extermination machine. She describes Polish Underground’s efforts to help Jews: establishment of Zegota office that provided money to Jews in hiding and rescued children from the ghetto and placed them in orphanages, private homes and monasteries. The Catholic Church supplied fake baptismal certificates. There was no assistance from the West.

This richness of facts and themes sometimes makes for difficult reading, which goes on for 600 pages. On display is the author’s command of facts and deep nuanced understanding of terror and suffering of Poles in occupied Poland, areas incorporated into the German Reich and the Soviet Union, the Gulag and outside theaters of war. The author also shows her deep knowledge by linking strands of past Polish and European history to wartime attitudes and policies. What makes it readable, if not to say fascinating, is the haunting stories of survival contained in personal interviews and fragments of memoirs. That illustrates that war is not only a military endeavor but has a lifelong impact on all those alive at the time.

Such careful examination of facts allows important judgments to be made that while often known in Poland were generally not accepted in the West. For example: the author demonstrates that Germany’s war against Poland was a total war from the very beginning and not as is widely assumed in the West a gentlemen’s war where mass murder was only committed against civilians with the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Kochanski shows that Germany bombed numerous small towns like Wielun with no military targets already on 1 September, widely machine-gunned rural roads crowded with refugees streaming east and immediately shot or imprisoned the political elite.

Polish defense plans were totally dependent on a Western counterattack within two weeks of the start of the war. But the Allies had no intention of countering Germany though they had 110 French and British army divisions as against only 23 German divisions in the West. Further, the British prevented the Polish Army from mobilizing in the last days of August when the war was imminent, while later criticizing chaotic Polish performance under German onslaught. This criticism was unwarranted in view of Western passivity, and even worse performance of the French Army in 1940 where Polish experience of German warfare was disregarded as escaped remnants of the Polish Army fought in France and later Britain. Poland not only contributed skillful pilots to the Battle of Britain but was also a pioneer of military parachuting. It organized a parachute brigade outside of the British Command to be used in the Polish Uprising. But when the Uprising came, the British insisted on using it in a drop on Arnhem where it was annihilated.

Throughout, the most important action happens in Poland itself. Kochanski divides the war in occupied Poland into three periods: the 1939-41 Soviet-German collaboration under Stalin-Hitler Pact, the 1941-43 German invasion of the Soviet Union, and the 1943-1945 Soviet offensive on Berlin. These periods marked differing occupation policies. The first period established the system of terror, the cooperation between the two occupiers in destruction of Polish elites, which culminated in the Katyn Massacre and the crowding of Jews into ghettoes. During this period Witold Pilecki, an emissary of the Home Army, entered newly constructed Auschwitz concentration camp to witness the brutal destruction of arrested Poles and later the industrial extermination of the Jews. Kochanski’s second period takes place after the invasion of the Soviet Union when Poland became more important to Germany strategically due to security considerations and lines of communications. This horrific period led to increased terror against the Poles, the worst of the war except for the Holocaust. The Wansee Conference of January 1942 established the German Generalplan OST, which envisaged the Final Solution to the Jewish question as well as the starvation of 80 percent of the local non-German population.

Kochanski’s third period (1943–1945) when the German Army failed to defeat the Soviets, led to a greater economic exploitation of Poland, including the reduction of food rations to starvation levels. Germans established concentration camps and labor camps in Germany and forcibly sent over a million Polish laborers there. They kidnapped 200,000 blond, blue-eyed Polish children. They started their OST plan to expel Poles from Poland and transfer German settlers there. The first region to be cleared was the Lublin province. In 1942–43, 31 percent of its inhabitants residing in several hundred villages, were murdered or deported to concentration and labor camps. 10,000 German settlers were brought in to replace them. The Home Army, however, attacked settlers who fled and it became impossible to farm. Germans destroyed 650 Polish villages in their collective reprisals for acts of sabotage. Ten percent of German forces were tied down by guerilla activities in Poland.

The Eagle Unbowed is an almost uniformly excellent treatment of the overwhelming devastation to the Polish people in the blood lands of Central Europe. It does indeed show a people who kept up the struggle in the face of terror, who remained unbowed. Certainly the subject material still has considerable blank pages in Stalinist history. Nevertheless, it is Kochanski’s great achievement to present an enormous and complicated story, much of it unknown in the West, in such a clear and balanced way. Importance of the Polish story lies in its shattering impact on the Western understanding of the war. Not only has Kochanski graphically portrayed most major issues of the war in Poland, she also leaves open the door for further discussion and comparisons with other countries.

___________________________________________

Lucja Swiatkowski Cannon has published articles on Eastern Europe in the Financial Times, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and other newspapers, professional journals, and books.