This is a story of a forgotten atrocity of World War II—a story of Polish Catholic priests. I focus on this group because I have observed that their story is relatively unknown, especially in the United States, and that they have not received adequate recognition in light of the great tragedy that befell them. This essay is, above all else, an evolving quest for the lost truth.

My inquiry began upon receiving a typewritten letter regarding the death of my great-uncle, Father Antoni Gerwel. While this subject is solely an academic matter for many, it is of a deeply personal nature for me. Like so many people with a connection to such tragedies, each time I sat down to express it in writing a rush of pain penetrated the depths of my heart, forcing me to stop long before I even began. Now, somehow, while staying in San Juan, a faraway, exotic place filled with sunshine, warmth, music, and celebration of life, I can write. I write calmly, exposing an aspect of humanity we fear most, namely death. Not a death of natural causes, but rather a senseless, pointless suffering inflicted by fellow human beings.

One day last fall, I remember asking my uncle Jedrzej, who lives in Poznan, Poland, to send me photographs of our family. To my surprise, a few hours later, I received a scan of a yellowed typed letter. I remember my frustration at being unable to read it fast enough, with its small, almost illegible font. But, slowly, a scene of horror and despicable tragedy unfolded before my eyes. I had always known that my family had suffered greatly during World War II, but I had never dared to ask of the extent.

Published below is my translation from the Polish language of the original letter written by Father Jan Żelaźnicki regarding the late Antoni Gerwel, a Catholic priest and my great-uncle, who was murdered on August 31, 1942, in Dachau concentration camp,

Dachau. General view of the camp.

Germany.

Kadzidło, July 22, 1977

Dear Sir Engineer:

In a response to your letter, dated the 15th of this month, I would like to provide you with some information regarding Father Gerwel. I have personally gotten to know Father Gerwel in Piekuty, where I gave a “sermon on indulgence.” Father Gerwel came to Piekuty from [the town of] Wigry, and after staying in Piekuty for several years, he moved to [the town of] Łyse in the neighborhood of Myszyniec and lived there for several years as well. Two years prior to the last war [WWII], he was in charge of Kadzidło Parish, also in the neighborhood of Myszyniec, in the county of Ostrołęka. Upon the outbreak of World War II, on April 9, 1940, while Father Gerwel worked in Kadzidło, he was arrested and deported by the Gestapo to Działdowo, along with his fellow priests.

Following his stay of nine days in Działdowo, he was taken to Dachau [concentration camp] along with me, in a transport of 1,500 prisoners. Following six weeks of quarantine in Dachau and a period of very hard labor in the construction of garages, once again, these 1,500 chosen persons were transported in cattle cars to Guzen, near Dunaj in Austria. On the way to camp Guzen, we were forced to run five kilometers by the Gestapo; we were beaten in such a manner that, as a result, 5 people died and 80 were wounded. Father Gerwel remained in Guzen, where he worked in a quarry, and I, in a group of 50 people, was transported to Mauthausen, the mother camp of Guzen.

We met again only on December 8th, 1940, in Dachau, where the Germans had relocated all the priests from various camps and placed them in three camps reserved for priests only. Living conditions there varied greatly. Beginning March 25, 1941, until perhaps September [of that year], we were given the privilege of not having to work and our living conditions improved slightly. However, soon thereafter, the Germans made up for their leniency many times over, such that the corpses of five priests were brought in daily, [once again due to imposed] labor.

At that time, Polish priests were forced to build a crematorium along with gas chambers; they were then the first ones to walk through those gas chambers and the crematorium [to be gassed and cremated], by the decision of the concentration camp administration. Meanwhile, a commando of invalids was being organized, under the banner of “improvement of life conditions,” in a special camp for the disabled, where the prisoners would be able to remain without working and with hope of a quicker release and return home.

Due to the scarcity of volunteers for this Gestapo proposal, a “general assembly” of the Polish priests was convened. At this time, [the Germans] selected a number of priests. In total, more than 500 priests were selected, along with the ones who volunteered.

Regretfully, they were not taken to an “improved camp for the disabled without work and with hope of returning home sooner,” but, instead, after several weeks, the disabled were separated and placed in a special “block.” Each evening, when the entire camp was asleep, 50 people [from the block] were taken to the baths, where they were told to undress; each of them was given denim trousers and a suit and then they were taken to mobile gas vans, in which they were poisoned on the way to the crematories.

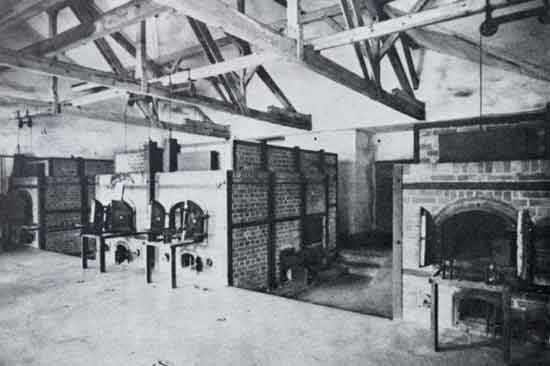

Ovens of Dachau

As soon as the gas chambers close to the crematories began functioning properly, the prisoners were poisoned there. 500 Polish priests were murdered in this manner. And so Father Antoni Gerwel also perished this way, but with a difference, since he died of natural causes—a stomach ailment—in the barrack of the disabled, after which he was cremated. On the whole, I would like to add (if I am not mistaken), Father Antoni volunteered for the camp of disabled. Prior to his being taken to the above-mentioned camp, I visited him, we said our farewells, and we both wished each other survival from the camp, the war, and a happy return to Poland. Regretfully, life took a different turn; I came back and he perished to God, whose faithful and exemplary servant he was.

I am not able to provide an address of anyone who knew your uncle, as all of our common friends are no longer among the living, and I don’t know the younger ones. As far as the files of the deceased are concerned, they can be found in Kurja Biskupia in Łomza, Sadowa Street #3, 18-400.

Ending this bit of news regarding Father Antoni Gerwel, I am enclosing all words of deserved respect,

Sir Engineer.

Father Jan Żelaźnicki

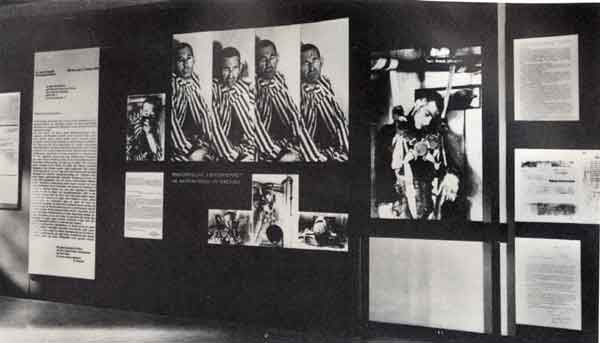

Photographs of victims of the camp prisoners in Dachau

I was mostly educated in the United States, having left Poland at the age of 12; after two years split between Libya, Tunisia, and Italy, I moved to New Jersey at the age of 14. I am still surprised at how little history concerning the suffering of Christian Poles during World War II is typically presented to American students.

In my New Jersey schools, we never learned the extent of the suffering that befell many European nations during the war.

Polish historian Roman Nurowski wrote as early as 1960, “As a result of almost six years of war, Poland lost 6,028,000 of its citizens, or 22 percent of its total population, the highest ratio of losses to population of any country in Europe,” of which, “approximately 4,384,000 or 89.9 percent, of Polish war loses (Jews and Gentiles), were the victims of prisons, death camps, raids, executions, annihilation of ghettoes, epidemics, starvation, excessive work, and ill treatment.”1 Historians today place Poland’s total wartime losses at around 2.9 million Polish Jews (nearly 90 percent of Poland’s Jewish population), 2 million ethnic Poles (around 10 percent of the total population), and 1 million of other nationalities, including Ukrainians and Belarusians.2

Also relatively unknown are the several pivotal resistance movements against Nazi Germany. Poland was one of the only occupied nations to continually resist Nazi forces for the entirety of World War II. This was carried out through the Polish Secret State, an underground political-military organization that operated from 1939-45.3 According to Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust museum, 6,394 Polish citizens, the most of any nationality, have been deemed “Righteous Among Nations” for their work protecting Jews during the Holocaust.4 Ŧegota (the Polish Council to Aid Jews), an underground organization active from 1942-45, was the only such organization in Europe. It helped save at least 4,000 Polish Jews during the occupation by providing safe hiding places, falsifying documents, and securing funds, food, and medications.5 Irena Sendler, a leading figure in

1. Nurowski

2. Piotrowski: 302

3. Marek Ney-Krwawicz

4. “The Righteous Among Nations,” Yad Vashem

5. “Zegota (1942-1945),” Jewish Virtual Library

Zegota, helped save 2,500 children from the Warsaw Ghetto.6 Other Polish military figures, such as Jan Karski, who reported on the terrible conditions of the Warsaw Ghetto and German concentration camps to the West, and Witold Pilecki, who volunteered to enter Auschwitz to report about it to the West, were until recently virtually unknown. Knowledge of many great tragedies, including the Katyn Forrest Massacre, in which 21,892 Polish officers were massacred by the Soviet army after April 3rd, 1940, has only resurfaced in the past several years.7

Agnieszka Gerwel is a staff member in the Department of Comparative Literature at Princeton University.

To be continue.