The presentation covered the region’s history under the relatively short-lived Nazi occupation, followed by a much longer communist one. This corresponds to the time period between the outbreak of the Second World War and the implosion of the Soviet Bloc: 1939 – 1989/92.

The epoch was undoubtedly the bloodiest in the Intermarium’s already turbulent history. Foreign invasions and devastating wars constituted a recurring theme. During the First World War, the fighting on the Eastern Front, which devastated the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, consumed four times as many military casualties as the trench warfare on the Western Front. Moreover, the much more mobile warfare between Germany and Austria-Hungary, on the one hand, and Russia, on the other, brutalized the civilian population as well. As a general rule, this contrasted with the treatment of civilians on the Western Front.

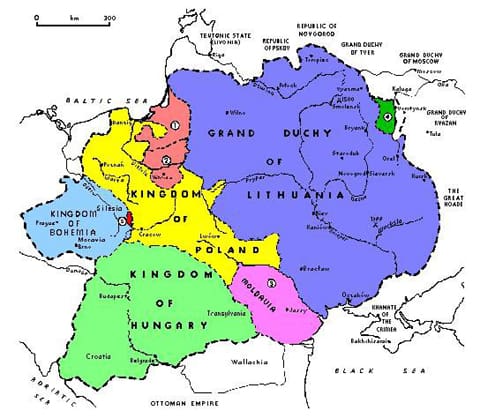

Yet, the 11 November 1918 armistice in the West failed to deliver peace in the East. The cruelty of the Bolshevik-sparked civil war in the defunct Romanov Empire – exacerbated by the revolutionary character of the struggle – spilled over into the Intermarium. Only the decisive Polish victories at Warsaw and on the Niemen River during the summer and fall of 1920 routed the Red Westward March, thereby preserving the independence of the „new” states resurrected or created as a result of the Versailles Settlement. In spite of this historical opportunity, the states of Central and Eastern Europe failed to unite, dissipating much of their energy on mutual conflicts. For a more detailed synthesis of Intermarium history during the interwar „false dawn,” please see the summary of Lecture No. 4.

Nevertheless, the problems plaguing the western and southern edges of the Intermariumpaled in comparison to the Golgotha forced upon its eastern edge by the Soviets. According to Soviet statistics, population growth projections fell short by 25 million people in the tally of 1938. This included the so-called „Polish Operation” of the NKVD, i.e. a genocide of 100,000-250,000 ethnic Poles settled near the USSR’s western frontier. Thus, the Bolshevik war against their subjects preceded any fighting with foreign states.

Meanwhile, few in the West foresaw the outbreak of the Second World War. Poland’s leaders realized that the country would eventually face a bitter struggle for its independence, but attempted to stave it off for as long as possible. Warsaw’s policy was based on an alliance with Britain and France and maintaining a „negative equilibrium” between both Germany and the Soviet Union. In fact, both of Poland’s powerful neighbors courted her during the late 1930s. Stalin offered to partition the Baltic states with Poland whilst Hitler promised parts of Ukraine in exchange for parts of western Poland (particularly the so-called „Polish corridor” in Eastern Pomerania). Warsaw rejected both proposals and was determined to resist. Prof. Chodakiewicz explained that the Polish decision to fight was decisively influenced by the country’s culture, shaped by romanticism and the legacy of chivalry. Moreover, much of Poland’s military elite was of common origin but was determined to emulate the martial bravery of the nobility of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The Poles prepared to repulse the increasingly bellicose Germans, no doubt expecting relief from their French allies. Meanwhile, the two totalitarian regimes surprised the world by signing the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, which carved up Poland and the Intermarium, and provided Hitler with a „green light” for aggression. The sudden alliance between heretofore ostensibly antagonistic revolutionary powers was a product of the adroit dialectical flexibility of totalitarian movements, Prof. Chodakiewicz emphasized. Quite simply, the consequentialist ethics at the heart of these radical ideologies proved capable of justifying any and all means of achieving the desired ends.

The totalitarian compatibility of both regimes was also reflected in strikingly similar policies in both occupation zones of Poland. Both the Soviets and the Nazis targeted Polish elites with the hope of decapitating the intransigent Poles. The number of executed Polish citizens on both sides of the new frontier was comparable. The Soviet-perpetrated Katyn Forest Massacre of April/May 1940 – a genocide of approximately 25,000 Polish officers and other members of the nation’s multiethnic elite – found its counterpart in German mass executions of Poles during the spring/summer of 1940.

Simultaneously, the Germans deported about 1 million Christian Poles from the western Polish provinces incorporated into the Third Reich into Central Poland, now dubbed the General Gouvernment. The Soviets deported 400,000 – 1.5 million prewar Polish citizens of all creeds into the Soviet interior, albeit in much more atrocious conditions. Many died in transit or due to exposure or exhaustion after reaching their destinations. Prof. Chodakiewicz elaborated that the lower estimates should be approached with skepticism because they are based on the official number of deportees expected per cattle car. Yet, the vast majority of survivors agreed that the actual number of „passengers” per railroad car greatly exceeded the official limit. Verifying these numbers is hampered by the dearth of microstudies and post-Soviet Russian unwillingness to declassify many relevant documents.

Were Berlin and Moscow coordinating their anti-Polish operations, or were these simply a product of the great similarities between the two systems? So far, insufficient evidence exists, although meetings between the NKVD and the Gestapo (such as the one in Zakopane) certainly took place during the period of the Nazi-Soviet alliance.

The severing of this totalitarian friendship as a result of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 brought further bloodshed to the Intermarium. Initially, the population from the Baltic to the Black Sea rose against their former communist oppressors, either spontaneously or in coordination with the Germans. Rough justice was dealt out to real and perceived Soviet collaborators, which sometimes degenerated into German-inspired pogroms of Jews, who were widely considered to sympathize with the communists. The retreating Soviets only added fuel to the fire by executing 20-40,000 prisoners.

The new occupiers quickly established their own order in the Intermarium. The locals were required to collaborate and various native auxiliary military and police formations were established. These were utilized to assist the Germans with such polices as the mass murder of the Jews. While many of these auxiliary policemen performed these tasks guided by anti-Semitism or the myth of Judeo-Communism, some (such as in Estonia) shot Jews simply as a result of political expediency (i.e. to please the Germans). In fact, the vast majority of Jews in the eastern Intermarium did not perish in gas chambers of concentration camps, but were shot in mass executions at sites such as Babi Yar near Kiev. Gas chambers were eventually devised because SS-men, in spite of their rabid, exterminationist anti-Semitism, suffered psychosomatic pain and other serious mental and physical disorders as a result of the mass slaughter, a reflection perhaps of the subconscious functioning of natural law within the human psyche. Prof. Chodakiewicz emphasized that the most important point to remember about the Holocaust, however, was that no single, written order to initiate the killing existed. Rather, theShoah consisted of a series of orders often conveyed orally. And the appetite grew as the mass slaughter engulfed the Intermarium.

The Christian population of the Intermarium suffered greatly as well. Peasants who failed to deliver the forced food quota or sheltered Jews were shot. The Germans also required that the locals perform onerous duties for them and deported many to forced labor in the Reich. Furthermore, vicious German pacification campaigns and punitive expeditions claimed untold lives as well. Last but not least, a Hobbesian struggle between the Germans, Soviets, and various native forces raged in the Intermarium. The Soviet partisans operated under direct orders from Moscow to provoke mass reprisals against the civilians to not only beef up their own ranks, but to spark a diversionary anti-German uprising. In addition, the communist guerrillas – sometimes consisting of desperate Jewish escapees from the ghettoes – robbed, exploited, and brutalized the villagers. The hard-pressed peasants responded by complaining to the local underground or the Germans, which further exacerbated the vicious spiral of violence. In the territories of the prewar Second Republic, Polish underground organizations were particularly active in combating the communists for the above reasons, in addition to opposing the Nazis. Further fanning the flames, Ukrainian ultra-nationalists, who had previously collaborated closely with the Nazis, began a massive ethnic cleansing campaign against Poles in Volhynia and East Galicia in mid-1943. It is estimated that the death toll of this genocide could have reached 120,000 people, including Ukrainians who sheltered Poles. Although the Polish side sometimes sought revenge by pacifying Ukrainian villages, these reprisals claimed a far smaller number of lives.

Meanwhile, in the wake of their victories at Stalingrad and Kursk, the Soviets began to reconquer the Intermarium from the summer of 1943. Thus, the region continued to bleed as the occupiers were once again swapped. The Soviet „liberators” perpetrated mass rapes, resumed deportations to the Gulag, and killed „fascist collaborators” – an infinitely elastic, catch-all category including local leaders and anti-communist underground members. Incidentally, the Soviets cynically incorporated all of the human losses suffered by theIntermarium into the Comintern-generated myth of „20 million Soviet/Russian war dead,” a cunning device to impress the Western conscience with the sheer scale of the Soviet contribution toward the victory over Hitler. Accordingly, the Soviet „sacrifice” included 3 million locals shipped by Stalin to the Gulag, the Jews of the Intermarium (in fact, the Jews of Wilno may have been counted three times: as Polish, Lithuanian, and Soviet Jews!), and Soviet deserters from the Red Army „repatriated” to the Socialist Homeland by the Allies.

Not surprisingly, much of the local population refused to regard the return of the Soviets as „liberation,” demonstrating their feelings through an anti-communist insurrection, which was the fiercest in the Ukraine, but spanned the vast swatch of territory from Tallin to Odessa and included Poland. It was not until 1949 that the communists destroyed the last significant Polish underground unit and the Soviets crushed the last major UPA unit only in 1955. Lone wolves held out even longer. The last Polish partisan was killed in action by the secret police in 1963 and the last Estonian „forest brother” perished to avoid capture as late as 1978.

In spite of the crushing of the armed underground resistance, anti-communist resentment seethed in the greater Intermarium. Thus, initially, most of the Communist Party cadre in the western Soviet republics (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova) consisted of ethnic Russian and other arrivals from the Center. Only later, as the weary locals succumbed to accomodationism, did the local ethnicities come to dominate the republican communist organizations. Even so, old wounds and aspirations for freedom and independence lingered. Gorbachev’s attempts to stave off the internal decay of the Soviet system during the late 1980s through various „reforms” and policies – such as Perestroika and Glasnost – unwittingly provided the channels for these pent-up frustrations.

The implosion of the Soviet Bloc and its impact on the Intermarium will be discussed during the sixth brownbag lecture on Wednesday, 16 November, at 2PM

Intermarium: Sovietization and Liberation

Start: Wednesday, November 16, 2011 2:00 PM

End: Wednesday, November 16, 2011 3:00 PM

You are cordially invited to a brown bag lunch with

Dr. Marek Chodakiewicz

On the topic of

Intermarium: Sovietization and Liberation

Wednesday, November 16

2:00-3:00 PM

The Institute of World Politics

1521 16th Street NW

Washington, DC 20036

Please RSVP to kbridges@iwp.edu.

This is the sixth lecture in the series entitled „Intermarium: The Lands on Edge,” sponsored by the Kosciuszko Chair of Polish Studies.

Dr. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz is the current holder of the Kosciuszko Chair of Polish Studies, which is now at IWP. He formerly served as an assistant professor of history of the Kosciuszko Chair in Polish Studies at the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, and as a visiting professor of history at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

He has authored numerous works in both English and Polish. While at the University of Virginia , he edited the Kosciuszko Chair’s bulletin: Nihil Novi. In addition to popular and scholarly articles, his publications include The Massacre in Jedwabne, July 10, 1941: Before, During, After (2005), Between Nazis and Soviets: Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939-1947 (2004) and After the Holocaust: Polish-Jewish Conflict in the Wake of World War Two (2003).

Source: