No other women’s team sport before or since created such a viable professional organization, tennis and golf, the most successful women’s professional sports, were still primarily amateur in the 1940s, without professional tours or associations. In order to succeed, a women’s professional sports enterprise had to overcome the cultural perception of sport as a masculine activity. Since the development of organized sport in nineteenth-century America, men had dominated virtually all athletic events and association, except for brief periods when women’s ; and swimming commanded a share of the limelight. College football, professional baseball, track and field, and boxing enjoyed large popular followings, while administrative bodies like the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the Amateur Athletic Union, and the National and American baseball leagues were led by men with little interest in women’s athletics.

Americans saw sport as a male activity, and they associated athletics with masculine ideals of aggressiveness, competitiveness, physical strength, and virility. Virtues for men, such traits raised the specter of „mannishness” in women. Doctors, scientists, and exercise specialists cautioned that sport posed grave emotional and physical dangers to women, issuing ominous warnings about female hysteria and damaged maternal capacity. However, some women braved the criticism and enthusiastically engaged in sports—from the 1890s bicycle craze to gymnastics classes, swimming, track and field, basketball, and especially Softball in the 1930s and 1940s. Advocates viewed sport as a step toward emancipation that granted them physical freedom and competitive experience denied under restrictive Victorian notions of femininity.

By War II, women athletes had established a solid institutional base in community recreation programs, industrial leagues, and instrumental school programs. Although proponents had by this time settled on a philosophy of “ modified athletics” for women, with special rules, uniforms and chaperone systems in place to differentiate women’s athletics from men’s, critics continued to evoke the image of the “mannish athlete.” Media portrayals frequently referred to successful athletes as „Amazons” with masculine skills and body types. At the organizational level, efforts to curtail women’s competitive sports and to eliminate female track and field events from the Olympic Games persisted through the 1950s.

To overcome resistance to their venture, Philip Wrigley and Arthur Meyerhoff did not try to reduce the tension between sport and femininity but instead decided to accentuate it. Meyerhoff especially sought to promote women’s baseball by capitalizing on the contrast between „masculine” baseball skill and feminine appearance, describing the league as a „clean spirited, colorful sports show”, built upon „the dramatic impact of seeing baseball, traditionally a men’s game, played by feminine type girls with masculine skill”. Meyerhoff speculated that the novelty of women’s baseball would attract first-time customers intrigued by the “amazing spectacle of beskirted girls throwing, catching, hitting and running like a men. . . .” Unlike barnstorming teams that occasionally featured women players competing against men, the AAGBL needed to sustain interest after the initial effect wore off. Meyerhoff again linked success to the combination of feminine charm and masculine activity. He believed that „the sight of girls playing baseball remains a constant source of amazement and wonder to most fans,” and „the fact that the All- American players are 'nice girls'” would give women’s baseball an edge over men’s in winning fan interest and sympathy.

The management did not consider athletic ability within the boundaries of femininity; they described baseball as a masculine activity and the girls’ league as a spectacle. The principal logic behind the league was to find women who played ball „like men,” not „like girls,” and who looked like „nice girls,” not like men. Why did Wrigley, Meyerhoff, and the team owners insist on this distinction? The answer lies in the broader history of sport as a male arena and, specifically, in the tarnished image of women’s softball.

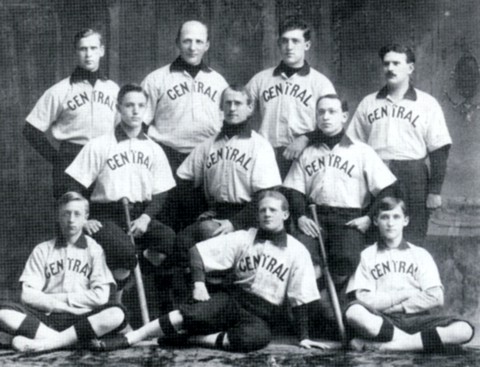

Softball, invented in the early twentieth century, provided an alternative to baseball that could be played in an indoor or restricted space. This Chicago team won, the Turner League championship for the 1907 -08 season.

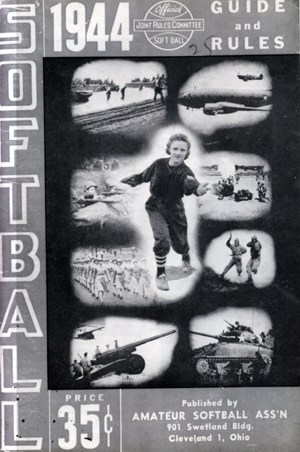

Invented in the early 1900s as a derivative of baseball for indoor play or in restricted outdoor space, softball came into its own as a game in the 1930s. The Amateur Softball Association (ASA) was organized in 1934, and after only one year 950,000 men, women, and children participated in ASA-sanctioned leagues. New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration poured money and workers into facility construction projects and community recreation programs.

Girls and women eagerly joined the throng. Unlike baseball, softball had no masculine stigma at first. If anything, the use of a softer ball, the smaller field dimensions, and early names like „kitten ball” and „mush ball” cast softball in a slightly feminine light as a game appropriate for women, youngsters, and men not rugged enough to excel in baseball.

Like the AABL, the Amateur Softball Association projected the idea that women were keeping the sport alive while men were away fighting the war.

To be continued.

Source: The Magazine of the Chicago Historical Society

Chicago History, Spring 1989, Volume XVIII, Number 1

No Freaks, No Amazons, No Boyish Bobs

Part I

https://polishnews.com/historia-history/chicago-history/4413-no-freaks,-no-amazons,-no-boyish-bobs