That money at one time could be eaten? Or that in South Carolina they once had legal tender you could drink? These are only a few of the many money innovations for which the creators of early currency deserve credit.

That woman’s picture, for example, came into view on a one-dollar 1854 bank note from the Delaware City Bank of the Kansas Territory.

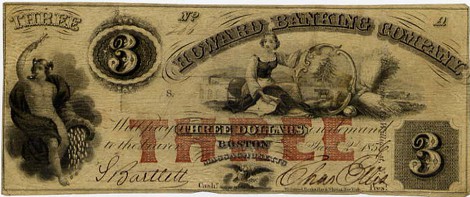

In 1856, also in Kansas, there were three-dollar bills! The notes featured pictures of three cherubs!

Salt, valuable as a food preservative, was scarce, durable, portable and easy to divide. Early Roman soldiers, whose Latin word for salt was „sal,” received a regular salt allowance (whence our word, „salary”), and slaves were sold for their weight in this precious condiment. Thus the expression „worth his salt.”

Liquors and other spirits have also served as money: beer was partial wages for miners in 19th century England; a century before, in South Carolina, rum was legal tender!

Tea, a common if blander beverage money, was used for centuries in the Far East. For ease in handling, it was often shaped into bricks.

Virginia, English setller harvest tobacco.

Over the centuries, money has been the subject of memorable quotations. „To have money is a fear; not to have it a grief,” said English poet George Herbert in 1651. According to Benjamin Franklin in 1735, „Nothing but money is sweeter than honey.”

In 1706, Jonathan Swift wrote: „No man will take counsel, but every man will take money: therefore money is better than counsel.” And an old Irish proverb had it that „a heavy purse makes a light heart.”

We are indebted to money for several everyday expressions such as „getting your money’s worth,” „the root of all evil,” „filthy lucre,” „money talks,” „putting your money where your mouth is,” and „putting your two cents in.”

What is more, there are local sayings relating to money in different countries with differing monetary units. American counterparts of these terms include „penny pincher” and „dollars to doughnuts.”

To coin an expression, banks have become „money-splendored things,” but few depositors realize how much banking has changed.

In the ancient world, instead of receiving interest on your savings, you’d have had to pay a bank to keep your money safe for you.

Perhaps the earliest American „bankers” were goldsmiths and silversmiths. They would accept coins for safe-keeping, and lend them to qualified borrowers, and sometimes exchange one kind of currency for another. That was it—no other services were available.

In 1781, when a man named Robert Morris tried to organize the first modern bank in America, he tried to sell $400,000 worth of stock in the company. All he could raise was $70,000—17.50 for each dollar he needed—but he borrowed what he needed from France, and made such a name for himself that almost any banker you visit today will know his name.

You can’t find money growing on trees, but another kind of money once did!

In 13th century China, when under the rule of Kublai Khan, the Chinese produced the world’s first paper currency, printed on paper made from the bark of the mulberry tree.

In the South Pacific, island tribes have used the teeth of porpoises, whales and tigers as money. On the Isle of Yap, huge coin-shaped stones with a hole in the middle—far too heavy for one man to lift—serve as currency. („I’m sunk,” a Yapper might have to say if he tried moving his money by canoe.)

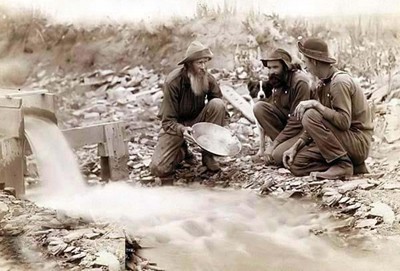

But few people know how an expression still used today began with an unusual form of payment in America’s Wild West. Then, many a man would carry currency in the form of a bag of gold dust. He’d pay for things by allowing the seller to pick out one or more pinches of dust. And this is how we get the expression, „How much can you raise in a pinch?”

Source: American Farm & Home ALMANAC

for the year of our Lord 1972