I enjoyed reading Laskin’s book, The Long Way Home: An American Journey from Ellis Island to the Great War, which was published early this year by Harper Collins. It’s a good book, long overdue, because it deals with immigrants from different backgrounds who fought under the American flag.

Unfortunately, the title isn’t entirely accurate. Neither Max nor Paul Cieminski, father and son, passed through Ellis Island. Max was not an immigrant himself. Paul Cieminski landed at New York in 1869, when Ellis Island was not yet an immigrant station.

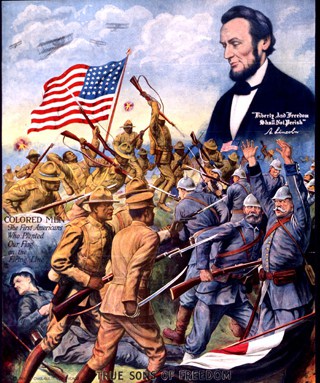

Recruting poster-World War I.

Due to the misspelling of his name, it is hard to find exactly when he acquired 80 acres of land in the village of Polonia, Wisconsin. For the first time, in 1872, when the first Polish settlers dismantled Sacred Heart Church at Poland Corners — the first Polish church in Wisconsin — and reassembled it at Polonia, without a foundation and a steeple, Cieminski was not listed among the taxpayers.

LIFE IN POLONIA

Taking a step out of the book, what evolved in Polonia is different from the embellishments of David Laskin. It all began in the middle 1850s, while hunting for deer and bears, that Joseph Oesterle, who came from Germany in 1849, found Indians camped around a shallow lake, 9.3 miles from Stevens Point, where he owned a lumber mill and manufactured shingles with his sons and other employees. Soon after, he built a log cabin and trading post on the edge of the lake and exchanged flour, sugar, coffee and other goods for furs and fish. Many Indians were still there when Father Dabrowski moved the first Polish church in Wisconsin to Polonia, as Poland is spelled in Latin. He labored to convert them to Christianity and, as early church records show, he baptized many Indian children.

According to an early plat of Polonia, Paul Cieminski owned 80 acres of primitive land on one end of Oesterle Lake (44.691°N 89.405°W), across the road from the old trading post. Joseph Oesterle, who eventually tore it down and built a frame building, became the first postmaster of Polonia. Most likely Oesterle, who amassed a large tract of land in the 1850s, sold a piece of it to Paul Cieminski and donated some of it to Father Dabrowski. When Sharon Township was created in 1860, surveyors laid out streets, including one between Lake Oesterle and the Indian trading post.

Maximilian, or Max for short, was the youngest of twelve children. He was born either October 11 or November 21, 1891, both of which were found in his records. His mother, Anna, was twelve years younger than Paul Cieminski, who was born April 1839. Paul and Anna Cieminski were married in 1870.

Paul Cieminski was a neighbor for the rest of his life with August Kluczykowski, a Civil War veteran, who raised fifteen children and a horde of grandchildren on his farm. It looked like Max walked to school and played with the war veteran’s grandchildren. No matter what they heard in English, whether they were Kaszubian, Polish, or something else in origin, no stories were dearer to them than those of the Indians on their land, Joseph Oesterle, and the gold coins he hoarded in his cellar. Oesterle’s daughter-in-law found the gold — $2,500 in five, ten, and twenty dollar pieces — while Max was growing up.

„The Third Sacred Heart Church, in Polonia, Wisconsin„

Another powerful influence in Polonia was the Sacred Heart Catholic Church. At 150 feet in height, the one built in 1903 was the tallest church ever built by Polish farmers in the United States and could be likened to St. Barbara’s Catholic Church at Lubon, five miles south of Poznan, Poland, where the Kluczykowski family came from in 1860. The church stood until it was hit by lightning and consumed by fire on St. Patrick’s day in 1934. The present edifice was built across the street, opposite the cemetery, and every August draws huge crowds to its picnics.

The Cieminski name was not really Kaszubian, as it is called in The Long Way Home, but derived from a Polish word, ciemny, which means dark. One finds Cieminski names practically everywhere in Poland. According to Polish government records in 2002, there were 109 persons who spelled their name without diacritical marks and 758 person who checked the letter n with a swoosh on top.

BREAKING UP

Over the years, in Polonia, where the Cieminski family watched Polish priests come and go, everybody thought they would prosper. But the children and grandchildren of the pioneers left one by one to seek a better life. Only Paul Cieminski, his son Bolelaus, and a married daughter, Janina Wysocki, with her spouse and children, remained in Polonia after Max joined his oldest sister, Mary, who was married to August Kondziela, and was a cook at their boarding house in Bessemer, Michigan. Kondziela, who came from Sangerhausen, Germany, in 1884, was also involved in a short-lived brewery.

While he was in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Max Cieminski found a job in the Newport iron mine, thousands of feet deep, not far from Bessemer, and shoveled red ore into tram cars until Uncle Sam called him into the service.

It is worth noting that, according to Max Cieminski’s draft registration on June 5 1917, none of his fingers were reported lost. Whether Laskin or a relative tried to sweeten the story, it was not necessary to lie that he had lost his trigger finger in a hunting accident. Max Cieminski lost his life on July 22, 1918, while fighting in France with Co. C, 102nd infantry regiment, to end the First World War. “The exact circumstances of Max’s death will never be known,” Laskin wrote..

BURIAL OF A HERO

Few, if any, books describe what happened to the bodies of 50,5110 soldiers, 431 sailors, and 2,461 marines, who were lost in the First World War. Thousands are still unknown. Boleslaus Cieminski played a very important role in his brother’s burial at Sacred Heart cemetery in Polonia, Wisconsin, which holds the graves of fourteen soldiers of the First World War. Until he died April 28, 1956, Boleslaus Cieminski remained in Polonia and tilled the soil in turn for his father, brother in law, and himself, and visited the cemetery as often as he could to pray, plant flowers, and cut the grass.

Were it not for him, the Cieminski family would not know that Max Cieminski, who received a gunshot wound in the head and lost his left arm and shoulder blade in combat, and didn’t have time to change uniforms, was buried without military honors in a 5-foot hole in the earth where he fell outside the village of Trugny, France. His grave was marked with his dog tags on a wooden cross. Investigators found a few witnesses to Private Cieminski’s death. On June 10, 1919, the body was dug up, with a set of honorary guards, and reburied in a cemetery with hundreds of unidentified soldiers. The cemetery, now known as Oise-Aisne Cemetery and the second largest American military cemetery in Europe, 75 miles northeast of Paris, contains the remains of 6,012 American war dead.

Bolelaus Cieminski arranged with the War Department to have his brother’s body returned to Wisconsin. The Long Way Home goes into detail. Funeral services were held at Sacred Heart Catholic church on July 26, 1921. For many years the family thought that the body was not that of Max Cieminski. Then it realized that their loved one was buried in the uniform of the 345th Infantry, to which he was first attached.

Hopefully, in the next seven years, when the centennial of the First World War is celebrated, someone will broaden the scope of our Polish war heroes. Authorative statistics for the number of Poles in the U. S. Army, Navy, and Marines are not available. In all, there were 4,057,101 in the Army, 588,051 in the Navy and 78,839 in the Marines during the First World War. The Army lost 50,51l in action. The Long Way Home set a fine example to follow.