Automobiles, buses, and trucks own our roads, and before them there was the horse. But in between-during the short golden age of cycling—the scorcher reigned supreme.

Part I

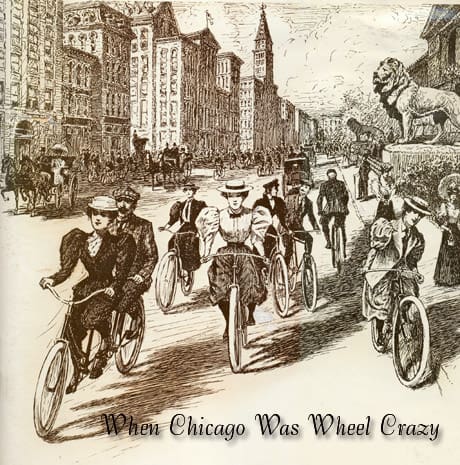

THE FAD OF CYCLING began with only a few- hardy males in the 1870s but, within twenty years, Chicagoans of all ages and both sexes were indulging in a heady love affair with the bicycle. By the 1890s, the „wheel” had become a means of both recreation and transportation for almost everyone with enough balance to stay on and enough strength to push the pedals. The entire city, it seemed, was caught up in the cycling craze.

In fact, for Chicago as well as the entire nation, the golden age of cycling had begun. In 1895, the normally reserved New York Times ranked the discovery and development of the bicycle as „of more importance to mankind than all the victories and defeats of Napoleon,” In April of that same year, a writer for Harper’s Weekly estimated that four hundred thousand bicycles had been manufactured since the first of January and predicted that production would continue to soar in 1896.

The precarious high-wheeler, or „ordinary” of the 1870s, had a six-foot-high front wheel which inspired little confidence in the observer as it rolled along Chicago’s streets or out into its countryside. The smallest stone or rut could pitch an unwary rider forward over the wheel to the ground in a nasty fall, steering was difficult, and a quick turn was almost impossible. The ordinary and the sport of cycling were the exclusive preserve of the adult male.

Developments in England were to change all this and make cycling a sport for everyone. In 1884, an inventor named John Kemp Starley designed the first „safety” bicycle, a machine with two much smaller wheels of equal size joined by a tubular frame. The rider sat on a saddle in the center of the frame and applied foot power to the pedals, which were connected to the rear wheel by a chain. A few years later, John B. Dunlop invented the pneumatic tire, which provided a far less bumpy, air-cushioned ride. American cycle makers also imported England’s lighter hollow steel tubing and, in 1894, the invention of the coaster brake completed the evolution of a bicycle very similar to today’s models.

Chicago in the Gay Nineties was an ideal climate for cycling. By 1893, there were a million and a half residents in the city proper, and two thousand miles of roads, many paved. Cyclists in or near industrial areas had additional incentives to mount their wheels. The air and the buildings of their neighborhoods were grimy from the ceaseless pall of smoke which hung like a low cloud, belched forth from factories, houses, and railroad yeards, and from the stubby steam engines which ran the „Alley El” route from Congress Street to the Columbian Exposition’s 63rd Street station. But escape was as close as Lake Front Park (now Grant Park), and to the north and west were tree-lined streets and an absence of industrial pollution, all easily reached by bicycle.

Best of all, the bicycle was relatively inexpensive. It cost far less than a horse, and it required little upkeep. In the Nineties, Chicago’s cyclists could buy a Columbia made by the Pope Manufacturing Company or an A. G. Spaulding for $100, An inseparable twosome could buy an American tandem, advertised at $150 in the Chicago Inter-Ocean, and bargain hunters could pick good used” Monarch for $50 or a „shop-worn model for $35.

Many customers preferred to buy a Schwinn, a Chicago brand still familiar to cyclists. Arnold Schwinn & Company was founded in 1895 by German immigrant Ignaz Schwinn and Chicago meat packer Adolf Arnold. At 29, five years earlier, young Schwinn had left a promising job at the Heinrich Kleyer cycle factory in Frankfort – on –the –Main to find opportunity in America. Attracted to Chicago by the city’s promise as a major bicycle manufacturing center, Schwinn worked first for Hill & Moffat, maker of the Fowler cycle, and then began Arnold, Schwinn & Company’s long career in rented space at the northwest corner of Lake and Peoria streets. The enterprise prospered, and the company bought the March-Davis Bicycle Company in 1899 at a receiver’s sale, moving to its site on Chicago western edge. In 1908, a new factory was built on adjacent land at 1718 North Kildare Avenue. It is still used as part of the ly’s assembly plant.

Accessories were more limited in the Nineties than now. The well-equipped cyclist bought a brass kerosene lamp for $2.25, a tire repair kit for a nickel, and a spare tire for $6.50. For 25 cents Rothchild & Company offered a double-stroke cycle bell. By 1895, nocturnal cyclists were buying the new carbide lamps fueled by acetylene gas to light the roads and ruts ahead.

West Madison Street became Bicycle Row in the 1890: there cyclists could buy a new or used wheel, have repairs made quickly, inflate tires, ” and perhaps even meet a young cyclist of the opposite sex.

Judy O’Grady and the colonel’s lady were equals on the bicycle, as Wheel Talk testified in 1895. Even Princess Maud of Wales, the magazine reported , „when she mounts a wheel, is no better off than other girls.” In May 1897, the Chicago Post reported that young society women were indeed awheel: „The fashionable girl no longer lolls about in tea gowns and darkened rooms, but stands beside you in short skirts, sailor hat, low shoes and leggings, ready for a spin on the wheel.”

Whether bloomers were proper garb, however, was a controversial matter, even among the women. By the late 1880s, the drop-frame cycle model was available to them, and the modified design did solve the problem of an entangled skirt, even though a typically brisk Chicago wind might suddenly blow a skirt back to outline the female cyclist’s limbs. Two lady cyclists, who prudently used only their initials, debated the bloomers issue in the Lake View Cycle Club’s monthly magazine The Cherry and Black for April 1896. Said the pro-bloomers writer, apparently something of a prophet, „We girls are not always going to stick around the home like they did olden times.”

Outing summed up the bicycle’s role in female emancipation in verse:

The maiden with her wheel of old

Sat by the first to spin

While lightly through her careful hand

The flax slid out and in.

Today her distaff, rock and reel

Far out of sight are hurled

And now the maiden with her wheel

Goes spinning round the world.

But the old guard died slowly. In June 1895, Gyda Stephenson, a teacher at Humboldt School, put on knickers cycled, and than wore the same garb into her classroom. In the ensuing skirmish with the school board, Stephenspn made it clear that what she chose to wear while cycling or teaching was entirely hefr affair.

Surprised by her resolute stand, the board dropped the matter.

Bloomers were a boon to the homely girl, according to a poet writing on the subject for the Sunday Inter-Ocean. He averred that although her face stopped not only clocks but streetcars as well, she found a solution:

And so she got some bloomers

And now with eager zest

She rides a cycle daily

And looks like all the rest

Not only the apparel manufacturers benefitted from the craze. Cosmetic manufacturers were also quick to seize an opportunity. To sell a variety of beauty aids-creams, pomades, and soaps—the merchants advertised their concern about the effect of wind and weather on delicate skin. One unguent, not content to advertise that it was „a sure and pleasant protection against the flying particles of sand, cinders, grit and other abrasives,” also informed readers that it was an effective shield against the „destructive rays of the sun.

Reprinted from Chicago History

The Magazine of the Chicago Historical Society

Fall 1975, Volume IV, Number 3