November 11, 1918, Poland regained independence after 123 years of partition and again appeared on the map. A day earlier, on a rainy morning, a special train from Berlin arrived in Warsaw. Jozef Pilsudski, freshly released from the Magdeburg Tower, was on board. The Germans kept Pilsudski’s arrival a secret, and only a few people welcomed him. Among them were Prince Zdzislaw Lubomirski, the representative of the Regent Council, and Adam Koc, the Commandant of Polish Military Organization (POW) in former Polish territories then under German occupation.

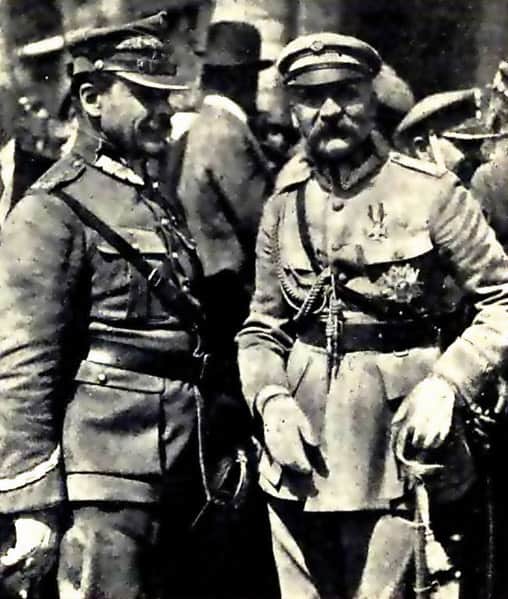

In some historical sources this event is called „the return from Magdeburg” and is often accompanied by a photo of Jozef Pilsudski with an enthusiastic crowd gathered around him. In reality, the reporter of Tygodnik llustrowany took this photo on a different occasion, in December 1916. In this case, legend took priority over fact. Such a photo was needed to satisfy a social demand.

The fact was that only a few people met that day at the Warsaw Railway Station. They represented two different worlds and times. One of them was a member of Regent Council who was known for his loyalty to Germans. He was of fading importance and relevance. The other was promoting the independence of Poland and he was the man to whom the future belonged. And finally, there was the man whose arrival the others were waiting for. He was a charismatic leader, who took upon himself the responsibility for renewal of the Republic of Poland.

To this day, Jozef Pilsudski is thought to be a creator of independent Poland. A large part of Polish society considers him as an iconic man, a role model, a man of morals and one of the most important Poles in history. However, some strongly oppose Pilsudski’s glorification. They argue that he was irresponsible with the power he held and very harmful to Poland. Golden legends about this man are often alternated with black legends. Both panegyrics and libels were written about him. Pilsudski always provoked strong emotions, be they good or bad. He possessed a persona that no one could be indifferent towards. Regular people are not worshipped to the degree he was and, conversely, not hated with as much vitriol.

How the legend grew…

The legend of Pilsudski started to emerge as soon as he began his political career as a socialist. At the beginning of the 20th century, Poles needed someone with charisma. The epoch of modernism „made the cult of the creative individual its central point. It was reflected in literature…by the introduction of strong, unique characters ” [Quotation from Marta Wyka]

Pilsudski did not automatically become a party leader of unquestionable authority. He had to earn it. Jozef Dabrowski, social activist from the beginning of the 20th century described it this way: „The first time I met Victor (Pilsudski’s nickname) I found him to be self-assured but friendly. His eyes were incredible. Thoughtful and pleasant, shadowed by joined brows, they seemed to be looking for more information. Viktor spoke with authority and true self-confidence. Throughout his whole career he always had fanatical supporters who would do anything for him. They would die for him if necessary. They thought his thoughts and believed everything he said.” Later in his life, Pilsudski’s opponents criticized his stubbornness, lack of manners, vengefulness, childish behavior and inability to communicate effectively.

Expected order of events

What Pilsudski and his socialist party were aiming to achieve – establishment of a Polish sovereign state – seemed to be infeasible at the time. Poland was incorporated into three neighboring countries: Austria, Russia and Prussia. As long as the European superpowers acted in agreement, no other political force could defeat them. Knowing that, Pilsudski was counting on a revolution or a war that would weaken those powers. In 1912, in Krakow he presented to other activists his anticipation of historical events. In his scenario, Pilsudski was counting on the world war that would put Austria and Germany against Russia. Russia would be defeated in the world. In the follow-up, England, France and the United States would successfully fight against Germany and Austria. His scenario was very close to what actually happened. According to Pilsudski, the Poles were to prepare themselves to take part in the war and wait for the right circumstances.

World War I

As soon as the war broke out, Poles started forming military legions. They fought on the side of Austria against Russia. Pilsudski, then the general of the brigade, was commanding the legions from 1914-1917.

About the same time Pilsudski and Wladyslaw Sikorski had their first conflict. (Later, during World War II, Sikorski was the head of the Polish government in London.) Pilsudski did not want Poles to be fighting on both sides, especially if the legions were fighting for the benefit of Russia. He suggested that Poles under Russian rule stop joining legions and present their demands to Russian leadership in a peaceful way. Lieutenant Sikorski had a different opinion on this subject and continued to recruit.

To strengthen his influence outside the frontlines Pilsudski started in July 1914, Polish Military Organization (POW), which soon became an important political tool in Polish hands. In 1915, after fighting Russian troops, Poles who supported Pilsudski established Central National Committee.

The war totally absorbed Pilsudski and brought to light certain aspects of his personality. Soon, he became a leader, with far more authority than other officers. This brought about some spiritual distance, but did not prevent Pilsudski from communicating with regular soldiers and lifting their spirits whenever there was a need to do so.

In May 1915, important changes took place on the east front. Polish legions were fighting Russian troops in Wolyn and trying to prevent Russian attack. Commander Pilsudski started to pressure the Austrians to conduct reforms in former Polish territories. As a result, Pilsudski was accused of not following orders and forced to resign. Other Polish officers then resigned in response to what they saw as an injustice. At the same time Polish Military Organization became more active and declared a willingness to fight against Russians but only under the command of Pilsudski. In those circumstances Germans and Austrians had to appoint Pilsudski to the Temporary State Council, which was a surrogate of the Polish government. When Pilsudski arrived in Warsaw he got an enthusiastic welcome from the people, who saw him as a national leader.

The turning point in Pilsudski’s politics was brought about by the February Revolution in Russia. His political strategy had been to fight with Russia and after the revolution it did not apply anymore.

The biggest enemy of Poland was out and now the Poles had to turn against two other occupants. The soldiers Polish Military Forces, (formerly known as Polish legions) refused to pledge loyalty to Austria and Prussia.

The reaction of the Germans was to arrest Pilsudski on July 21, 1917 and jailed him in Magdeburg Tower. In a political sense, this was good for Pilsudski because for the remaining months of the war he did not have to cooperate with Austria or Prussia.

The Chief of the State

Revolution in Germany brought freedom to Pilsudski. In the next few days the Regent Council gave the former prisoner the whole civil and military power. As Prince Lubomirski admitted: „All political parties from the furthest right to the radical left demanded from us that all authority be given to Pilsudski.” Local authorities in Krakow and Lublin recognized the leadership of Pilsudski.

On November 22, 1918, Pilsudski and Moraczewski (who was appointed as the Prime Minister) signed the Decree on the Highest Representative Power in the Republic of Poland. The document confirmed that Pilsudski would have the highest authority in Poland as Temporary Chief of State until the Diet would be elected. In fact, this document gave Pilsudski the authority of a dictator.

Demilitarization of Germans

Poles took upon the demilitarization of Germans even before the return of Pilsudski. In this action Polish Military Organization played a crucial role, taking over the important buildings. Demilitarization of the German garrison in Warsaw was one of the biggest challenges. All the officers and regular soldiers, who agreed to surrender their weapons, were guaranteed personal safety. This helped to avoid bloody confrontations and unnecessary loss of lives.

The development of the authority structure

Initially Pilsudski supported the leftist cabinet of Moraczewski but was not enthusiastic about it. Then gradually Pilsudski started to withhold his support for the leftist parties. This strategy was not aimed however against the working class or to protect the interests of the bourgeoisie. Pilsudski was thinking in different categories. He thought that for Poland the best government would be one in which different political forces could be joined together. Such a government could use the energy of various social groups in the name of the higher interests of the state.

The wars on the borders

Poland re-emerged in 1918 but it did not have well-defined borders. The Poles had to fight in order to define the territory. Pilsudski was aware of that and that was why he put a lot of emphasis on the army organization. During the first three years after re-emergence Poland won eight big and small wars on the borders. Upper Silesia and Wielkopolska became part of the new Poland as a result of national uprisings. The newly established state won a war with Ukraine and incorporated Lwow and Eastern Malopolska. The Poles defended the country well during the attack of Czechs on Cieszyn Silesia and against the Lithuanians in the Suwalki area. Pilsudski was unable to include his Lithuanian homeland into the new country. His politics worsened the relations betweens Poles and Lithuanians. The most dramatic was the war with the Bolsheviks in defense of Polish independence.

The battle of Warsaw in 1920 had a tremendous international meaning. As Earl D’Aberon, British ambassador in Berlin, pointed out, Pilsudski’s victory prevented the Soviet Army from invading the rest of Europe. The Warsaw battle stopped the Russians from destroying Western civilization.

Pilsudski died on May 12, 1935. His heart was buried in his mother’s grave in Vilnius and his body in the Wawel Chapel in Krakow next to the kings and queens.

By: Aleksander Wietrzyk

Tr. Anna Witowska-Ritter

.jpg)