Agnieszka Gerwel is a staff member in the Department of Comparative Literature at Princeton University

In the midst of this great Polish catastrophe, the Catholic Church was especially targeted. The introduction to the memoir of Father Kazimierz Majdanski, the late archbishop emeritus of Warsaw and a Dachau survivor, reads:

Forgotten… in most of the world is the Nazi’s attempted obliteration of the cultures of occupied countries, and their paranoid reaction to any organized group perceived as constituting an ideological threat. In Poland, one of the groups the Nazis feared most was the Catholic Church. Because the Church was embedded in Polish society, with clergy well educated and respected by the people, the Nazis could not tolerate this institution in a country that they planned to radically redesign. Their goal, therefore, was to destroy it.8

Aside from playing an important religious role, the Polish Catholic Church was, most importantly, a political and cultural pillar spanning over 1,000 years of Poland’s history. As such, German occupiers understood that killing priests and destroying the church would be, ultimately, the most effective way to undermine the social and cultural foundations of the Polish nation.

1. Tomaszewski and Werbowski

2. Snyder: 415

3. Anderson

The Nazis began by burning library collections and museums, along with private and public archives, religious art, writings, and documents. Thousands of priceless religious manuscripts perished in this manner at the outset of World War II.9 Tragically, this destruction soon spread to the religious officials themselves.

The Roman Catholic Church was suppressed much more harshly in Poland than in other places under German occupation. Germans closed the majority of Polish churches, and priests were arrested en masse without legitimate reason. Arrests of the clergy began in the first half of October 1939, in the wake of the Nazi invasion of Poland. Most priests were held in prisons, under awful conditions, after which they were transferred to various concentration camps in both occupied Poland and Germany.

Under the AB-Aktion (the “Extraordinary Pacification Action”) of 1940, Nazi Germans targeted the Polish intelligentsia to create a state of terror and annihilate Polish culture from the very onset of the war. Because they were seen as “the most serious obstacle in the way of Germanization,” over 3,500 Polish professors, doctors, teachers, judges, clergy, and other educated persons were killed in regional actions, and several thousand more were imprisoned.10 In addition, over 1.5 million Polish citizens were deported to Germany as slave laborers, according to the United Nations postwar analysis of Displaced Persons.11

Having witnessed the allied liberation of Dachau, William W. Quinn, a colonel in the 7th U.S. Army, described the camp:

Dachau, 1933-1945, will stand for all time as one of the history’s most gruesome symbols of inhumanity. There our troops found sights, sounds and stenches horrible beyond 9.

See the work of Polish historian Anna Jagodzinska, a specialist on the topic of martyrology of Polish priests for the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw.

1. Nurowski: 79-80

2. Hitchcock: 256

belief, cruelties so enormous as to be incomprehensible to the normal mind. Dachau and death were synonymous.12

Opened in Bavaria on March 22, 1933, by the order of Heinrich Himmler, Konzentrationslager (KZ) Dachau is known today simply as Dachau. Completed in 1935, its pre-war purpose was to isolate political opponents of the Nazi regime, but during the war it expanded to detain Jews, clergy, and others.13

It was the first concentration camp constructed on German soil and a prototype for the others that followed. KZ Dachau was the camp where the Nazis sent most arrested priests from across Europe, including Germany itself. It was also the center for the extermination of the Polish clergy. In his 1975 history of Dachau, historian Paul Berben wrote of the clergy detained in the camp:

The fate of the Poles was especially hard. Archbishop Koslawiecki said in 1960 that in Auschwitz (where he spent some time before his four years at Dachau) he considered the day to have been a good one if he had been slapped only once or twice:

‘For years we got up when it was still dark; for years we went to roll-call and to work with heavy and anxious hearts…

They also tried to kill our souls. We were strictly forbidden to pray or carry on any religious activity at all. Anyone who tried to confess or hear confession was very severely punished.’14

Priests, such as my great-uncle, sometimes lived in such conditions for years, and many thousands of them perished. Ultimately, an estimated 95 percent of the 4,618 clergy imprisoned were Roman Catholics and 65 percent were Poles, of which 2,801 perished during the Nazi occupation—866 of them in Dachau alone.15

1. William W. Quinn in “Dachau,” a 1945 American wartime pamphlet

2. Berben: 3

3. Berben: 148

4. Piotrowski: 302

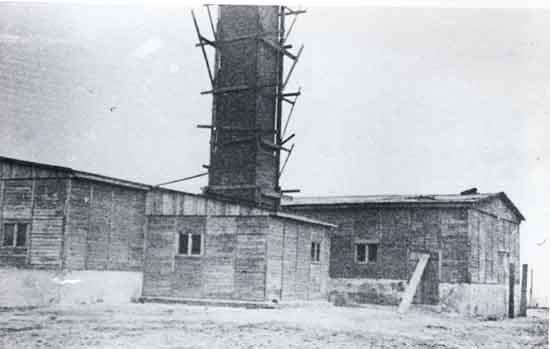

Dachau crematory

Ever since I received the letter, I have tried to imagine how my great-uncle lived day-to-day in the last two years of his life, spent in Dachau. I read about likely aspects of his daily routine, including forced labor, starvation, torture, medical experimentation, and the camp’s notorious roll calls that entailed hours of standing in the freezing cold. But what I have come to understand most clearly is that, despite “the routine,” daily life in the camp was always unpredictable. Nothing made sense, and no one was certain of what would take place at any given moment. Any visit from German camp commandos could mean instant death, for a variety of reasons, some of them quite banal—for example, if a Nazi officer did not like someone’s facial expression, their height or their voice, or if they placed their hands in their pockets. The Nazis maintained an environment of constant terror for the inmates—an incredible stress and disregard for life that ultimately lead to my great-uncle’s death.

In order to properly comprehend what took place in Poland during World War II, it is pivotal to recognize all available information and account for all its atrocities. Through my great-uncle’s story, I hope to have shed light on one such human tragedy—one that ought to never have taken place, but one which we must now acknowledge and attempt to understand.

Letter on a Polish Priest in Dachau

Works Cited

Anderson, Carl A. Introduction to Archbishop Kazimierz Majdanski. You Shall Be My Witness: Lessons Beyond Dachau, trans. Maria Klepacka-Srodon. New York: Square One, 2009.

Berben, Paul. Dachau: 1933-45, The Official History. London: Norfolk, 1975.

Hitchcock, William I. The Bitter Road to Freedom: The Human Cost of Allied Victory in World War II Europe. New York: Free Press, 2008.

Ney-Krwawicz, Marek. “The Polish Underground State and Home Army (1939-1945),” trans. Antoni Bohdanowicz. London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. http://www. warsawuprising.com/state.htm.

Nurowski, Roman. 1939-1945 War Losses in Poland. Ponzan and Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Zachodnie, 1960.

Piotrowski, Tadeusz. Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998.

Quinn, William W. in “Dachau,” American wartime pamphlet, 1945.

“The Righteous Among Nations.” Yad Vashem. http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/statistics.asp.

Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010, p. 415.

Tomaszewski, Irene and Tecia Werbowski. Code Name Ŧegota: Rescuing Jews in Occupied Poland, 1942-1945, the Most Dangerous Conspiracy in Wartime Europe. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010.

“Ŧegota (1942-1945).” Jewish Virtual Library. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/Zegota.html.

PART I

http://ru.polishnews.com/historia-history/historia-polskipolish-history/4828-letter-on-a-polish-priest-in-dachau