In the old country, one could spell their last names without any trouble and accent them with dots, hooks, legs, and other attributes. Up in the mountains, however, the names were not as good as wine, and legions of Polish immigrants, who came to mine coal in the bowels of the earth, received numbers because no one could spell their last names.

For the descendants of Joseph Rotkiske, the least of his worries was a family tree. No words were needed to convey the importance of having one. He did nothing to change the proliferation of spellings. Teachers spelled it one way, priests another, stonecutters still another, and census takers much less cared how they spelled it. No one in the family was able to go ahead in genealogy without knowing the true identity of the progenitor. “It’s very difficult,” one of them said. “Not just for the present name of the family, but for finding marriage licenses, births, death records, passenger lists of ships, and everything else.”

FAMILY TREE

Rotkiske was a mysterious name. It was not a pure Polish surname. The venerable bearer of the name had eleven children, all born in Reading, Pennsylvania, and not all of them stuck around long enough to find out his mother’s first married name and his stepfather’s proper name. This is essentially the story of the names that were lost, forgotten, buried, or whatever they were up in the mountains in the early part of the twentieth century.

Since Joseph Rotkiske’s death in 1978, more persons have come into the family and rapidly spread the Rotkiske name around like drifts of snow. In public records, for example, I found 48 different addresses for nine persons of the same name. The women who came into the family by marriage were apparently more curious than the opposite sex, for one of them, Rayleen Rotkiske, the wife of a truck driver for 25 years, told me that the name intrigued her. “My husband is Polish,” she wrote, “I am not. I have always been interested in his

heritage. His ancestors came here and shortened their last name.”

Strangely, without knowing it, Joseph Rotkiske, who was Rayleen’s

father-in-law’s father, lost his own name and that of his stepfather in Shamokin. His daughter, Dolores, has a box of his papers with different spellings of his last name. In his final years, he took her to visit his half sister, Stella Antonelli, who lived in Brady, a tiny village between Shamokin and Kulpmont, and the graves of his stepfather and a half brother, whose first name was Frank, in St. Casimir’s Cemetery, on top of a mountain between Kulpmont and Marion Heights, which was as close anyone came to finding out his last name when he was born March 19, 1890, and in 1899 when his mother changed her last name again by marriage.

LIFE ON HORSEBACK

To pick up the pieces where Dolores left off, I started with Joseph

Rotkiske’s stepfather. Very little is known of the 26 years he spent in this country during a time of amazing growth in the coal industry. His name popped up in the 1910 census of West Cameron Township, in the lower reaches of Northumberland County, where the dwellers relied on horses to plow their fields and travel to work, church, and do other things. The township of 11.8 square miles was sparsely settled, with 60 married women and 373 persons in 1900 and slightly more in 1910, all except one born in Pennsylvania, and did not the include the school teacher. More stunning was the picture that, although it had no coal mines, two thirds of the families in the township had someone who picked slate in a coal breaker or shoveled coal in the mines. It meant that each one had to walk or ride a horse to work.

As the census taker filled in the blank spaces, Frank Rutkoski, a 45-year-old coal miner, who came from the Russian partition of Poland in 1884, was married twelve years. His wife, Mary, 42 years old, who came from the same part of Poland in 1899, raised six of eight children. Only three children, however, were listed — Joe, 19 years old, who came to the U. S. in 1899, and was a laborer in the coal mines; Stella, 9 years old, born in Pennsylvania, and Frankie, 7 years old, born in Pennsylvania.

All that changed in the next ten years. The abbreviation, “wd,” which stands for widower, was written after the father’s name in the 1920 census of Shamokin. For obvious reasons, Joseph enlisted December 21, 1911, at Shamokin in the U. S. Army. If it wasn’t the worst place for slaughtering Polish names, Shamokin, where the first Polish church in Pennsylvania was built in the early 1870s, has to be one of them. In this case, the census taker spelled the father’s name Rotokski and the army officer the stepson’s name Rotkiske. The proper spelling was, of course, Rutkowski, as 41,363 Polish citizens signed their last name in 1990.

Instead of training him to fire cannons, the U. S. Army assigned Joseph Rotkiske to take care of the horses at Fort Slocum on an 80-acre island between Long Island and New Rochelle, New York, and saddle them for the military officers. Later in life, when he had a riding academy in Berks County, Pennsylvania, he taught all his children and others to ride horses.

BRANCHING OUT

Upon his discharge in 1914, he returned to Shamokin, where his stepfather worked in the mines, and years later met Josephine Dudek, who came from Bedziemysl, Poland, in 1914, when she was nine years old, and courted her until they were married in Reading on June 12, 1922. The Dudek family, owing to changes in employment and death of the breadwinner, spent time in Reading and Shamokin.

When Joseph Rotkiske moved to Reading, his wife opened a grocery store in the neighborhood of St. Mary’s Catholic Church, where they were married, and carried a lot of customers on the books. Their inability to pay their debts after the crash of Wall Street forced her to close the store.

It was during this time that Joseph Rotkiske saw an opportunity to expand his business of drilling water wells and installing cesspools. Many Polish families in Millmont, who had left St. Mary’s in 1914 to establish another Polish parish in Reading, were then without running water and a sewer system. They had their own wells and privies. The church itself — called St. Anthony of Padua — and the school in the basement had no modern facilities until 1940, and one wonders whether there were outhouses for priests, Bernardine Sisters, church goers and school children in the infancy of the parish.

After four boys and a girl were born in the city proper, the Rotkiske family moved to Millmont, where six more children were born. The fourth male, also named Joseph, who was born April 9, 1925, expanded the Rotkiske clan when he married Verna D. Griswold. They eventually had two daughters and six sons, and they scattered to nearby towns. When the head of the family died in the emergency room of Reading Hospital, Feb. 18, 2006, they brought twenty grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren to the funeral Mass at St. John the Baptist de La Salle R. C. Church in Shillington. On the male side, the six sons not only added their unusual name but also added to the prosperity of different communities.

The third Joseph in the family enriched Birdsboro; Edward, Mohnton; Michael A., Sinking Spring; Arthur D., Shillington; Robert D., Tamaqua; and Dennis J., Philadelphia.

It would take another time to tell the story of each one. At this moment, no one stands out more than the first Edward Rotkiske in Reading. Uncle Sam brought him into the war in 1943. His body was never found on the Solomon Islands in the Pacific, where he fought the Japanese army, and hopefully it will be.

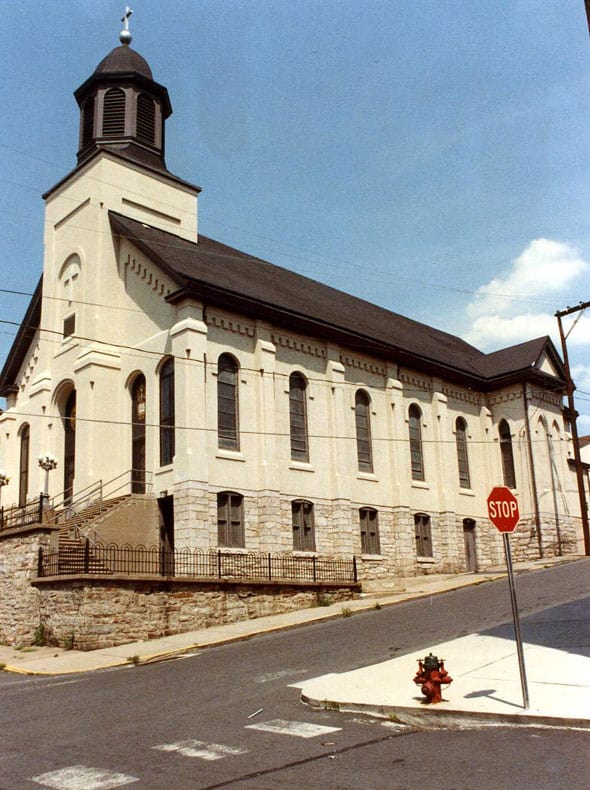

In 1899, Frank Rutkowski, who came from Poland in 1884, married a

widow, three years younger than he was, at the first Polish church established

in Pennsylvania — St. Stanislaus, Shamokin, shown here — and presumably she

was buried about 1910 at St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Trevorton, where the first

Polish colony in the coal fields of Pennsylvania was formed as early as 1852.

Photo by Edward Pinkowski