A more detailed report on his journey is given by Maisky himself [8, p. 369-371]. According to his memories from 1965, his plane left England on July 3, around midnight, to land on Gibraltar on in the morning of July 4. At midday his Liberator took to the air and proceeded eastward to continue the journey. Usually, a plane flying from Gibraltar to Cairo had one landing stage at the aerodrome of Castel-Benito, near Tripoli, but that time it went a little farther. Maisky’s plane landed at a military airport in the desert around 6 p.m. on July 4, 1943.

According to Maisky, his plane was to leave around midnight and reach Cairo on July 6, at 7 a.m., but this seems to be not credible. The route from the military airport to Cairo would take around 31 hours, which is technically unreliable. His story seems to be suspicious. It is also possible that Maisky left Gibraltar not on Sunday, July 4, but Monday morning, July 5.

Even more improbable is Maisky’s explanation of the reason for the landing, not at Castel-Benito, but at the aerodrome in the Libyan Desert. According to Maisky, Sikorski’s plane departed on the morning of July 5 from Cairo and the ambassador himself had left Gibraltar by that time. This way he admits that he left Gibraltar not at noon on Sunday, but on the morning of Monday, July 5 [8, p. 371]. It was obvious why Maisky’s plane didn’t land at Castel-Benito. At that time Polish government didn’t have diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia, and the British, afraid of further „misunderstandings”, decided to prevent Maisky from meeting Sikorski, and designated two different airports for them to land. So to hide the truth, Ivan Maisky had to say that General Sikorski wasn’t present in Gibraltar on July 4 as he was in Cairo until July 5. Unfortunately, that kind of miracle never happened. This is proof that Ambassador Maisky was shuffling.

This is how General Sikorski’s friend Karol Popiel, Polish parliament deputy in 1922-1927, one of the most prominent Front Morges members and a member of General Sikorski’s government, describes the Gibraltar catastrophe in his book [10, p. 190]: “One thing is sure for me beyond any doubts: General Sikorski’s death wasn’t an accident. It was planned and it was supposed to happen on his way to the Near East. That plan wasn’t fulfilled, but it succeeded six weeks later.”

There are facts that prove that Lieutenant Lubienski’s description the events accompanying the death of General Sikorski was not truthful. After Lubienski died, his daughter Rula Le?ska, a well-known in England actress, said in one of her interviews: “I’ve got a feeling that my daddy was buried keeping a big secret in his heart“ [2, s.43]. Gralewski’s wife, Alicja Iwanska, in 1982 published his so-called letter-fragments [3]. On July 4th, 1943, at 6 p.m., Gralewski wrote [3, s. 198]: “Well, this phase is ending and it ends unexpectedly impressively. Tonight I’m leaving Gibraltar. I’m afraid the older gentleman [Sikorski] will tell me off for my conversation in Madrid. But I’ll defend myself. Moreover, there are high hopes for a bright future… only a little bit… it’s close… I can hardly write, too many feelings, too many thoughts. Finally I‘ve reached that stage of intensity of life that it makes insight impossible. Maybe later, perhaps in the future – and it will be a hundred times more exciting – I’ll be able to describe what’s happening today.” Nothing indicates that the real Jan Gralewski met General Sikorski on that day. Gralewski would describe his meeting with Sikorski. It was somebody else. It is obvious that Lieutenant Lubienski, introducing somebody else to Sikorski, was aware of the mystification. In the book mentioned above, Alicja Iwanska recalls her conversation with Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz, a professor and long time friend of her husband, who in his 1945 book “Remembering Past Philosophers, 1939-45” would write that: “Jan Gralewski died in the Gibraltar catastrophe together with General Sikorski”[3, s.6]. Iwanska disagreed, saying that: “(…) every death is a private death of an individual, and any attempt to bind Gralewski with Sikorski, either for sensational or prestigious reasons, would take his own death away from him.” Her statement leads to the conclusion that Jan Gralewski wasn’t killed in the plane crash, but died in a different way.

The same was stated by Tadeusz Kisielewski. Alicja Iwanska in the autobiographical novel called “Niezdemobilizowani” (Not Demobilized), in which her husband bears the moniker Marek, wrote: “It was so-called luck, that Marek did not struggle a lot; as they say, death from a bullet is easy: a sharp pain and a brief moment of consciousness.” [4, p.85]

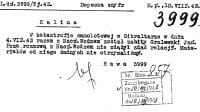

From the documents of Jan Gralewski’s file in the Polish Institute and Museum of General Sikorski [1], we learn that he came with Boleslaw Kozlowski to Gibraltar on June 23, 1943. These names are on the list of passengers of the British cruiser „Carnival” and a battleship from Villa Real to St. Antonio to Gibraltar. In remarks on that list it says Jan Gralewski left under the name of Jerzy Nowakowski, and Boleslaw Kozlowski left under the name of Wiktor Suchy. The same kind of list, from the same ships, but dated on July 23, 1943, contains the names of Wiktor Suchy and Jerzy Nowakowski. In remarks on that list it is stated that Wiktor Suchy left under the name of Boleslaw Kozlowski, and Jerzy Nowakowski left as Pawel Palkowski.

Jan Gralewski became a foreign courier on October 25, 1942, and started passing through to France [3, p. 168]. He went there for the first time in late November 1942 and came back before Christmas [5, p. 224]. His wife, Alicja Iwanska, was already working for an underground organization army (AK) “Lza-24”, taking care of couriers traveling to France [3, p. 169-170]. At the beginning of January 1943, Gralewski left on another courier’s journey. His wife’s task was to take care of the couriers getting ready for a journey and coming back from it. She didn’t help Gralewski as it was against the rules of conspiracy. Iwanska was also providing couriers’ families with money during the time they were on the mission.

By the end of January 1943, Gralewski came back from the assignment only to leave on February 8 under the pseudonym Pankracy for his last mission from Poland. The Polish Underground State sent him to establish the track to Spain for couriers. While Gralewski was away, Alicja Iwanska was taking care of Boleslaw, another foreign courier much older than her husband [5, p. 228]. That Boleslaw might have been Boleslaw Kozlowski. In a conversation with a Polish Home Army courier, Alicja Iwanska learned that Gralewski, after a failed attempt to get from Paris to Vichy, was redirected to get to Spain through the Pyrenees [3, p. 171]. On May 27, 1943, Jan Gralewski was taken to Miranda del Ebro, a Spanish concentration camp [3, p. 186]. He was hoping to be there for only 2 weeks, but he stayed in Miranda del Ebro until June 23 – the day he came to Gibraltar. As Alicja Iwanska states, most probably Gralewski left the camp thanks to the British [3, p. 171]. He wasn’t well-oriented in his plans as he wrote in a so-called letter-fragment to his wife dated June 30:”Tomorrow we’re going to be shipped to England”.

The tragic fate of Jan Gralewski is probably a key to solving the mystery of General Wladyslaw Sikorski’s death. Tadeusz Kisielewski, in the article titled “The mystery of the tragedy in Gibraltar,” mentions the rumor noted by Rev. Antoni Frugala in August 1943, about a secret order “telling every Polish officer to shoot Wiktor Suchy, Polish Armed Forces officer”[6]. Unfortunately, the author didn’t reveal the source of this information.

Bibliography:

1. Archiwum Instytutu Polskiego i Muzeum im. gen. Sikorski, Londyn, Archives Ref. No A.XII. 4/172.

2. Bzowska Katarzyna, Jedna noc w Gibraltarze, „Nowy Dziennik”, New York, July 4-6, 2003, p. 42-43.

3. Iwańska Alicja, Gralewski Jan, Wojenne Odcinki, Warszawa 1940 – 1943, Oficyna Poetów i Malarzy, London 1982.

4. Iwańska Alicja, Niezdemobilizowani, Poznań – Warszawa 1945-46, Polska Fundacja Kulturalna, London 1988.

5. Iwańska Alicja, Potyczki i Przymierza, Pamiętnik 1918 – 1985, Gebethner i Ska, Warszawa 1993.

6. Kisielewski Tadeusz A., Tajemnice tragedii w Gibraltarze, Cz. I. „Mówią Wieki” 2001, nr 12, s.23-28: Cz. II „Mówią Wieki” 2002, nr 1, p. 23-27.

7. Lubienski Ludwik, The last days of General Sikorski: an eyewitness account, in: Sword Keith (editor), Sikorski: Soldier and Statesman, A Collection of Essays, Orbis Books (London) Ltd., London 1990.

8. Maisky Ivan, Memoirs of a Soviet Ambassador, The War: 1939-43, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1968.

9. Niebelski Eugeniusz, Dobrze zasłużony Ojczyźnie. W 120 rocznicę urodzin generała Władysława Sikorskiego, „Rocznik Mielecki” 2001, t. IV.

10. Popiel Karol, Genera? Sikorski w mojej pamięci, Odnowa, London 1978.

11. Szafran Czesław, Kontrowersje wokół katastrofy gibraltarskiej, w: Moszumański Zbigniew, Zuziak Janusz (red.), Generał Wladysław Sikorski, Szkice historyczne w 60. rocznicę śmierci, Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Toru? 2004.