„Justice has been done,” President Barack Obama said in a dramatic announcement at the White House.

The military operation took mere minutes, and there were no U.S. casualties.

U.S. helicopters ferried troops from Navy SEAL Team Six, a top military counter-terrorism unit, into the compound identified by the CIA as bin Laden’s hideout — and back out again in less than 40 minutes. Bin Laden was shot in the head, officials said, after he and his bodyguards resisted the assault.

Three adult males were also killed in the raid, including one of bin Laden’s sons, whom officials did not name. One of bin Laden’s sons, Hamza, is a senior member of al-Qaida. U.S. officials also said one woman was killed when she was used as a shield by a male combatant, and two other women were injured.

The U.S. official who disclosed the burial at sea said it would have been difficult to find a country willing to accept the remains. Obama said the remains had been handled in accordance with Islamic custom, which requires speedy burial.

„I heard a thundering sound, followed by heavy firing. Then firing suddenly stopped. Then more thundering, then a big blast,” said Mohammad Haroon Rasheed, a resident of Abbottabad, Pakistan, after the choppers had swooped in and then out again.

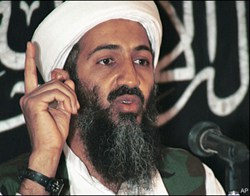

Bin Laden’s death marks a psychological triumph in a long struggle that began well before the Sept. 11 attacks. Al-Qaida was also blamed for the 1998 bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa that killed 231 people and the 2000 attack on the USS Cole that killed 17 American sailors in Yemen, as well as countless other plots, some successful and some foiled.

In all, nearly 3,000 were killed in the Sept. 11 attacks nearly 10 years ago, the worst terror assault on American soil.

Moments after Obama’s dramatic late-night announcement on Sunday, the State Department warned of the heightened possibility for anti-American violence. In a worldwide travel alert, the department said there was an „enhanced potential for anti-American violence given recent counterterrorism activity in Pakistan.”

As news of bin Laden’s death spread, hundreds of people cheered and waved American flags at ground zero in New York, the site where al-Qaida hijacked jets toppled the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Thousands celebrated all night outside the White House gates.

As dawn came, the crowd had thinned yet some still flowed in to be a part of it. A couple people posed for photographs in front of the White House while holding up front pages of today’s newspapers announcing bin Laden’s death.

As dawn came, the crowd had thinned yet some still flowed in to be a part of it. A couple people posed for photographs in front of the White House while holding up front pages of today’s newspapers announcing bin Laden’s death.

„It’s a moment people have been waiting for,” said, Eric Sauter, 22, a University of Delaware student who drove to Washington after seeing TV coverage of the celebrations.

The development seems certain to give Obama a political lift as the nation swelled in pride. Even Republican critics lauded him.

But its ultimate impact on al-Qaida is less clear.

The greatest terrorist threat to the U.S. is now considered to be the al-Qaida franchise in Yemen, far from al-Qaida’s core in Pakistan. The Yemen branch almost took down a U.S.-bound airliner on Christmas 2009 and nearly detonated explosives aboard two U.S. cargo planes last fall. Those operations were carried out without any direct involvement from bin Laden.

The few fiery minutes in Abbottabad followed years in which U.S. officials struggled to piece together clues that ultimately led to bin Laden, according to an account provided by senior administration officials who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the operation.

Based on statements given by U.S. detainees since the 9/11 attacks, they said, intelligence officials have long known that bin Laden trusted one al-Qaida courier in particular, and they believed he might be living with him in hiding.

Four years ago, the United States learned the man’s identity, which officials did not disclose, and then about two years later, they identified areas of Pakistan where he operated. Last August, the man’s residence was found, officials said.

„Intelligence analysis concluded that this compound was custom built in 2005 to hide someone of significance,” with walls as high as 18 feet and topped by barbed wire, according to one official. Despite the compound’s estimated $1 million cost and two security gates, it had no phone or Internet running into the house.

By mid-February, intelligence from multiple sources was clear enough that Obama wanted to „pursue an aggressive course of action,” a senior administration official said. Over the next two and a half months, the president led five meetings of the National Security Council focused solely on whether bin Laden was in that compound and, if so, how to get him, the official said.

Obama made a decision to launch the operation on Friday, shortly before flying to Alabama to inspect tornado damage, and aides set to work on the details.

The president spent part of his Sunday on the golf course, but cut his round short to return to the White House for a meeting where he and top national security aides reviewed final preparations for the raid.

Two hours later, Obama was told that bin Laden had been tentatively identified.

CIA director Leon Panetta was directly in charge of the military team during the operation, according to one official, and when he and his aides received word at agency headquarters that bin Laden had been killed, cheers broke out around the conference room table.

Administration aides said the operation was so secretive that no foreign officials were informed in advance, and only a small circle inside the U.S. government was aware of what was unfolding half a world away.

In his announcement, Obama said he had called Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari after the raid, and said it was „important to note that our counterterrorism cooperation with Pakistan helped lead us to bin Laden and the compound where he was hiding.”

One senior administration told reporters, though, „we were very concerned … that he was inside Pakistan, but this is something we’re going to continue to work with the Pakistani government on.”

The compound is about a half-mile from a Pakistani military academy, in a city that is home to three army regiments and thousands of military personnel.

Abbottabad is surrounded by hills and with mountains in the distance.

Critics have long accused elements of Pakistan’s security establishment of protecting bin Laden, though Islamabad has always denied it, and in a statement the foreign ministry said his death showed the country’s resolve in the battle against terrorism.

Still, bin Laden’s location raised pointed questions of whether Pakistani authorities knew the whereabouts of the world’s most wanted man.

Whatever the global repercussions, bin Laden’s death marked the end to a manhunt that consumed most of a decade that began in the grim hours after bin Laden’s hijackers flew planes into the World Trade Center twin towers in Manhattan and the Pentagon across the Potomac River from Washington. A fourth plane was commandeered by passengers who overcame the hijackers and forced the plane to crash in the Pennsylvania countryside.

Former President George W. Bush, who was in office on the day of the attacks, issued a written statement hailing bin Laden’s death as a momentous achievement. „The fight against terror goes on, but tonight America has sent an unmistakable message: No matter how long it takes, justice will be done,” he said.

Associated Press writers Erica Werner and Ben Feller contributed to this story.